What is Poitín? Ireland's 'Illegal' Moonshine Explained

For centuries, Irish governments tried to kill it. The English banned it repeatedly. Parish priests denounced it from pulpits. Yet poitín — pronounced "pot-cheen," Ireland's original moonshine — refused to die. Made illegally in remote cottages, distilled by firelight in copper vessels passed down through generations, it became the spirit of resistance and rural resourcefulness.

In 1997, after 336 years of prohibition, Ireland legalized poitín. Today you can order it in Dublin pubs, visit licensed distilleries, and bring bottles home as souvenirs.

But legal poitín and traditional poitín are different animals. The legal version is regulated and taxed, bearing little resemblance to the fiery spirit that defined rural Irish life. The real stuff — if you can find it — still carries the danger and mystique that made it legendary.

This guide explains what poitín is, why it was banned, where to taste authentic versions safely, and how to avoid tourist traps selling overpriced imposters.

What Is Poitín? The Basics

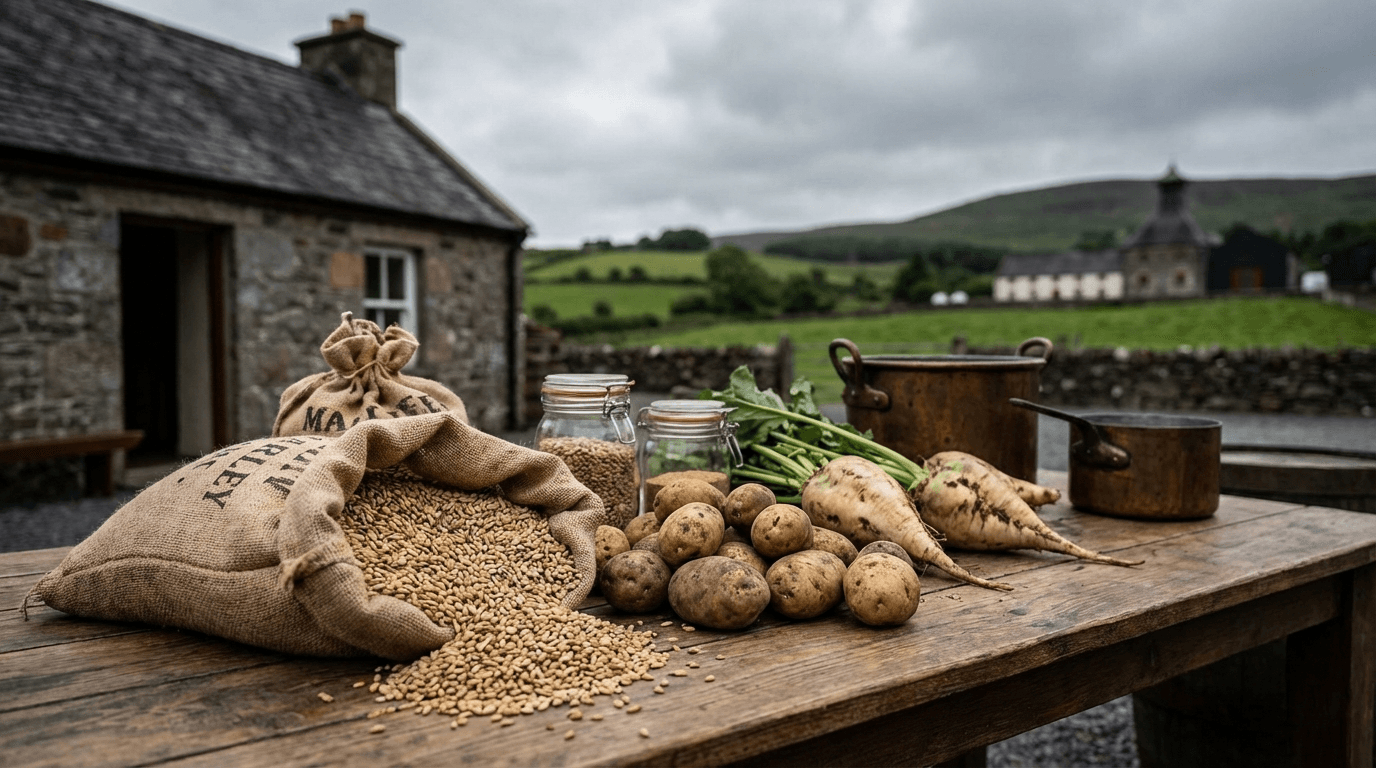

Poitín is Irish moonshine — illegally distilled spirit made from fermented grain, sugar beet, potatoes, or treacle. The name comes from the Irish "pota," meaning pot, referring to the small copper stills used in production. Pronounced "pot-cheen" with stress on the second syllable.

Traditional poitín runs 60-90% alcohol by volume (120-180 proof) — standard whiskey is 40% ABV. Rural drinkers diluted it with water, milk, or mixed it into "poteen tea" with sugar and spices.

Base ingredients varied by region: malted barley in grain areas, potatoes in the west, sugar beet where grain was scarce. Each recipe created distinct regional variations — Connemara poitín tasted different from Kerry or Donegal versions.

What unites all traditional poitín is the production method: small-scale, illicit, and illegal. Distillers worked at night to hide smoke from authorities, hiding stills in remote locations. The copper pot stills were often portable, dismantled when the "poteen men" (Gardaí excise officers) came calling.

Why Was It Banned? A History of Resistance

Poitín's prohibition began in 1661 when the English Crown imposed a tax on distilled spirits. Irish distillers ignored it, refusing to pay foreign occupiers for the right to make their own alcohol. The ban wasn't about public health — it was about money. The English wanted excise revenue. Irish distillers wanted autonomy.

The result was 336 years of cat-and-mouse between authorities and producers. By the 18th century, poitín production was ubiquitous across rural Ireland. Contemporary accounts suggest nearly every parish had multiple stills. Quality varied wildly — some was excellent, some toxic.

The Gardaí established "poteen men" — excise officers who specialized in finding and destroying illegal stills. These officers became folklore figures, portrayed as bumbling Englishmen outwitted by clever Irish peasants. The reality was often darker: violent confrontations, seized farms, prison sentences.

Poitín persisted because it served essential social functions. In cash-poor communities, it was currency — traded for goods, used to pay laborers, offered as hospitality. It was medicine — believed to cure colds and arthritis. It was celebration — required at weddings, funerals, and harvests.

The ban lifted in 1997, with licensing beginning in 2008. Today, legal poitín must meet the same standards as other spirits. The wild west era is officially over, though traditional producers still operate in remote areas.

Legal Poitín vs. Traditional Poitín: Know the Difference

Walk into an Irish pub today and order poitín, and you'll likely receive one of two things: a licensed commercial product or — if you're in the right place with the right connections — a pour from an unlabeled bottle that someone's cousin brought from a farm in Connemara.

Legal poitín is produced by licensed distilleries under regulations governing whiskey, gin, and vodka. Micil Distillery in Galway produces award-winning versions. But it's not traditional poitín historically — it's distilled in legal facilities to predictable standards (usually 40-50% ABV) and taxed.

Traditional poitín — made in remote cottages and hidden stills — still exists in a legal gray area. Technically illegal without a license, Gardaí rarely pursue small-scale producers unless they cause public health issues. Traditional poitín persists, passed between friends and hidden from official view.

The taste difference is significant. Legal poitín tends toward clean, neutral spirits — high-proof vodka with subtle character. Traditional poitín is unpredictable: sometimes smooth, sometimes harsh enough to strip paint. Each batch reflects its maker, location, and ingredients.

For tourists, legal poitín offers safety, consistency, and the ability to bring bottles home. Traditional poitín offers authenticity and stories — but also health risks from improper distillation.

Where to Taste Poitín Safely: The Legal Options

If you want to experience poitín without risking blindness or prison, several licensed producers offer excellent, authentic versions:

Micil Distillery, Galway is the gold standard. Located in Connemara — historically prolific for poitín — Micil has made spirits since 1848 (legally since 2016). The current distiller, Pádraic Ó Griallais, is sixth generation using 170-year-old family recipes.

Micil offers tours (£20) covering history, production methods, and tastings. Their standard poitín is 44% ABV. They also produce versions infused with bogbean, heather, and local botanicals. The tour ends in their tasting room overlooking Galway Bay.

Mad March Hare, Dublin produces cocktail-focused poitín from malted barley and sugar beet. Find it at The Liquor Rooms or 9 Below.

Knockeen Hills, Waterford offers the strongest legal poitín — Gold Strength reaches 90% ABV (180 proof). A thimbleful diluted with water reveals complex flavors. Available in specialist off-licenses.

Bán Poitín, Belfast brings Northern Irish traditions to legal production with small-batch seasonal releases, sometimes peat-smoked.

The Pub Scene: Where to Order Poitín in Ireland

Beyond dedicated distilleries, several Dublin and Galway pubs specialize in poitín or carry interesting selections:

The Palace Bar, Dublin — Serving Dublin since 1823 with excellent poitín selection and knowledgeable bartenders.

The Blue Light, Dublin — Dublin Mountains pub with poitín history connections and Micil stock.

The Crane Bar, Galway — Traditional music pub with impressive poitín selection.

Tigh Neachtain, Galway — Established 1894 with Connemara producer emphasis.

Practical tip: When ordering, specify neat, diluted, or in a cocktail. Neat poitín can overwhelm newcomers. Poitín and ginger ale is a traditional mixer. Cocktails treat it like high-proof rum.

Safety: How to Avoid the Bad Stuff

The danger isn't alcohol content — it's improper distillation creating methanol (wood alcohol), which causes blindness and death. Historical poitín deaths were rare, usually involving inexperienced distillers.

Modern risks are lower but real. Here's how to protect yourself:

Buy from licensed producers when possible. Micil and other legal brands meet safety standards with labeled alcohol content and tax stamps.

In pubs, ask provenance. If offered "traditional poitín" from unmarked bottles, ask where it's from. Vague answers warrant caution.

Examine the liquid. Quality poitín should be clear. Cloudiness suggests contamination. An oily sheen indicates improper distillation.

Smell before drinking. Proper poitín smells alcoholic but clean. Chemical or acetone smells suggest problems. Trust your nose.

Start small. Traditional poitín might be 60-80% ABV — double whiskey's strength. Sip, don't gulp. Dilute with water. Eat first.

Know methanol poisoning symptoms. Headache, dizziness, nausea, and visual disturbances within 12-24 hours are warning signs. Seek medical attention immediately if suspected.

Most traditional poitín today is safe, made by experienced producers. But the unregulated nature means caution is essential.

Poitín in Irish Culture: More Than Just Booze

Understanding poitín requires appreciating its cultural significance beyond intoxication. For centuries, it was woven into rural Irish life:

Medicine — Before modern pharmaceuticals, poitín was Ireland's universal remedy. Applied externally, it treated arthritis and muscle pain. Taken internally, it supposedly cured colds and digestive issues. Many Irish over 60 recall grandparents administering "poteen cures."

Currency — In cash-poor economies, poitín was liquid currency. Laborers accepted it as payment. It settled debts and sealed deals. A bottle of good poitín opened doors that money couldn't touch.

Hospitality — Refusing poitín when offered was historically insulting. The ritual of sharing created bonds between strangers and cemented friendships.

Resistance — Poitín symbolized Irish refusal to submit to English rule. Every illegal still represented defiance. The drink acquired romantic associations with rebellion and national identity.

Literature and folklore — Poitín appears in Irish writing from Flann O'Brien to traditional songs. The "poteen maker" — wily and resourceful — became an Irish archetype.

This cultural weight explains why poitín survived centuries of prohibition. It wasn't just alcohol; it was identity and autonomy.

The Verdict: Should You Try Poitín?

Absolutely — with appropriate caution. Poitín offers a direct connection to Irish history that polished whiskey tours cannot match. This is the drink of rebels, poets, and farmers. It's messy, dangerous, and authentic.

For cautious tourists: Start with Micil Distillery in Galway. It's safe, educational, and genuinely excellent.

For adventurous drinkers: Seek traditional poitín in rural Galway, Mayo, or Donegal pubs — but apply safety checks. Start with tiny amounts and trust your senses.

For enthusiasts: Compare both. Notice how production methods affect flavor. Understand why this spirit mattered enough to risk prison for 336 years.

Whatever you choose, approach poitín with respect. This isn't gentle whiskey for casual sipping — it's Ireland's wild child, finally legal but still carrying centuries of rebellion in every drop.

The Water of Life: The Ultimate Guide to Irish Whiskey & Breweries — the master hub — covers Ireland's full spirits landscape, from Jameson and Bushmills to Dublin's craft distilleries and this most Irish of drinks. Whether you visit Micil's legal operation or chance upon traditional poitín in a Connemara pub, you're tasting history.

Just arrange transport before you start tasting. The Drink Driving Laws in Ireland apply to poitín just as strictly as whiskey — and at 60-90% ABV, the margins for error are vanishingly small. A Private Driver lets you explore Ireland's poitín heritage without risking your license, your safety, or your holiday.

Sláinte.

---

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.