Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

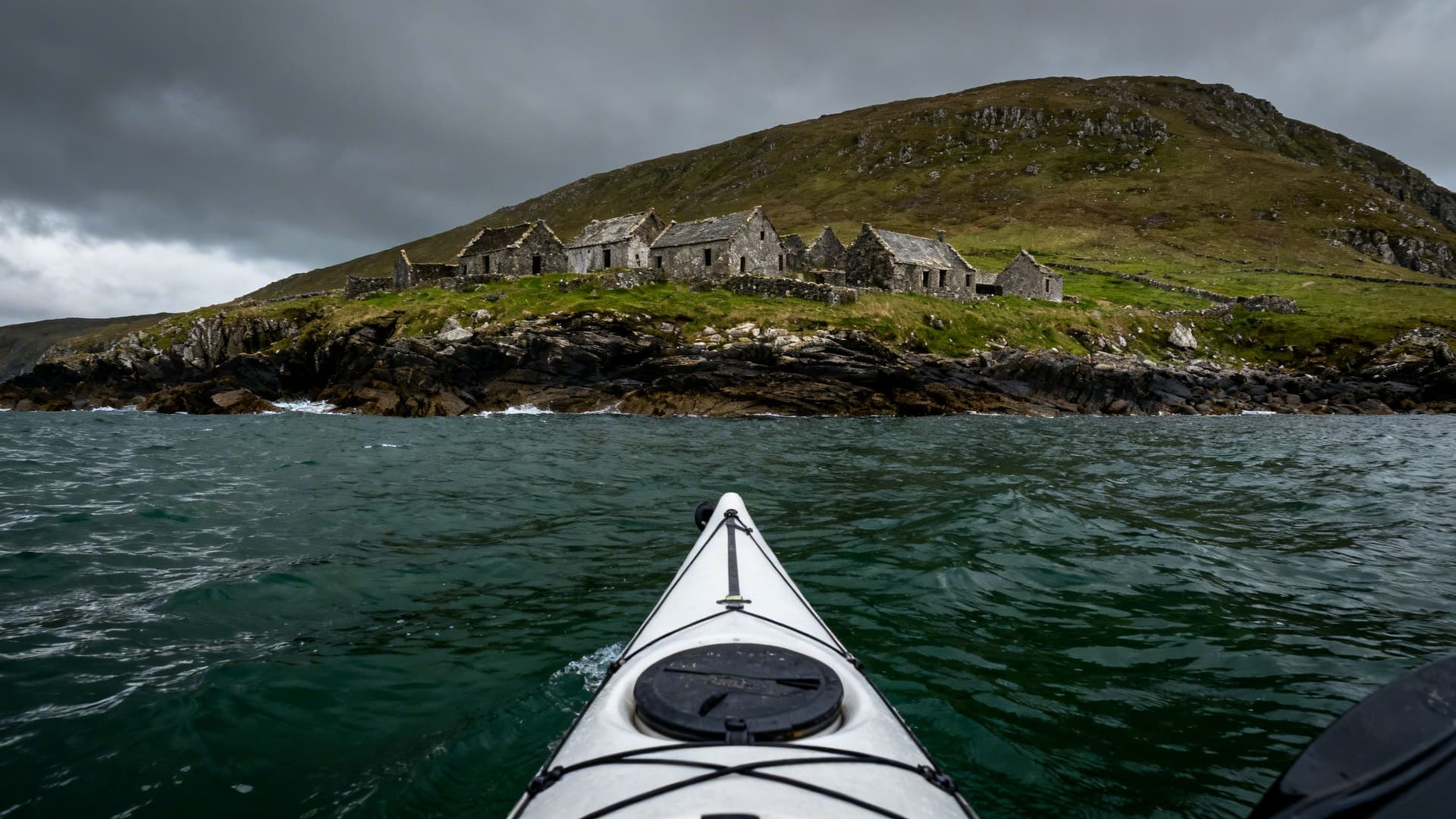

There's a car park at Dunmore Head at the western tip of the Dingle Peninsula where you can stand and look at the Blasket Islands across three kilometres of open ocean. The islands are close enough to see the ruined stone walls of the village on Great Blasket's eastern slope. Most people look for about five minutes, take the photograph, and drive back to Dingle for lunch. From a sea kayak at the base of the cliffs below that car park — 300 metres of sea-stained rock above you, the Atlantic open ahead — you are in a completely different relationship with this place.

The Dingle Peninsula is 50 kilometres long, faces fully west, and has a geography that seems designed for the water: a sheltered south shore, a wilder north shore opening onto Brandon Bay, sea caves in the headlands that the road above them never reveals, and a stretch of ocean between Dunmore Head and the Blasket Islands that carries more history per cubic metre than almost anywhere in Ireland. For travellers building a broader itinerary along the Irish coast, Sea Kayaking in Ireland: A Complete Guide covers the full range of what's possible and where. This is the specific guide to what the Dingle Peninsula offers from the water — and why it rewards a local guide in ways that no map quite captures.

The Peninsula from the Water: What the Road Doesn't Show

The Ring of Kerry gets the coaches. Dingle gets the people who did their research.

From the road — even from the clifftop viewpoints at Slea Head — you see the tops of things. The headlands from above, the sea as a view rather than a surface. From a kayak, you're in the space between the land and the open Atlantic, and the scale of what this coastline is takes on a different quality. The cliffs at Slea Head drop vertically into deep water. You paddle between them and the open sea, looking up at something that most visitors never look up at from this angle.

The south shore from Dingle town to Slea Head runs sheltered under the peninsula's mountain spine. It receives the afternoon light, and in calm conditions the water is clear enough to see the bottom in the coves between headlands. The north shore from Clogher Head around to Brandon Point faces northwest, where the prevailing Atlantic swell arrives, and can build quickly as the morning progresses. Most guided sessions work the south shore and the Slea Head headland — consistently rewarding paddling without requiring open-water experience — while the north shore is reserved for days when the forecast says so.

The Sea Caves at Slea Head: Timing Is Everything

Between Dunmore Head and Slea Head, the cliffs are riddled with caves that the road above them doesn't know about. From the water, you find them by paddling close to the base of the rock and watching for where the swells push into shadow.

The largest of the caves at this headland runs deep enough that the light changes as you enter — from full Atlantic brightness to a dim turquoise glow as the water reflects the ceiling. The sound changes too: the slap of waves against rock echoes back from ahead, which is how you know you're inside something substantial. In certain conditions, bioluminescence in these waters makes the paddle strokes glow a cold blue-green in the darkness of the cave interior.

What determines whether you can enter them is the swell. A metre of Atlantic swell that feels unremarkable in open water becomes a different force when it's surging into a rock chamber with limited exit. The caves at Slea Head are accessible in windows that shift by the hour — not something you work out from a tide table the night before, but an assessment made at the water's edge by someone who has read this specific stretch of coast across all its moods. That knowledge is the defining difference between a guided session here and arriving independently with a hired kayak.

The Blasket Sound: Paddling the Last Parish

Great Blasket Island sits three kilometres off Dunmore Head — close enough to see the ruined stone walls of the village on its eastern slope, far enough that the crossing is a serious undertaking in any conditions that aren't calm. The Blasket Sound runs north-south between the island and the peninsula, and the tidal flow through it is strong and variable.

The Great Blasket was inhabited until 1953, when the remaining 22 islanders petitioned the Irish government to move them to the mainland. The community had been losing people to emigration for decades before that — many to Springfield, Massachusetts, where a Blasket Island diaspora community took root deep enough that it persists to this day. The island was a living place, a Gaeltacht community with its own literature, within living memory. The ruins you see from the water are not medieval. They are a generation old, and the people who left them had descendants who may now be booking flights back to see where their families came from.

Paddling through the Sound with Great Blasket off your left shoulder and the Atlantic opening to the southwest, you are in the water that shaped everything that left from here. You cannot land on the island from a kayak without a guide who knows the landing conditions — the currents and the swell behaviour on the island's eastern shore change the picture entirely from what it looks like from the water. On the right day, with the right guide, it is possible.

What Lives on This Coast

Dingle Bay has a resident population of bottlenose dolphins. They're not guaranteed on any given session — they travel unpredictably through the bay — but some sessions on the water produce an encounter that no itinerary planned for: a group surfing a swell a hundred metres ahead of you, then gone before you've properly processed what you saw.

Grey seals are more reliable. They haul out on the rocks below the cliffs on the south shore and watch passing kayaks with the particular expression of animals who have decided you are probably not a threat but haven't fully committed to that position. The standard advice is to maintain a respectful distance, which turns out to be unnecessary — given enough stillness on the water, they approach on their own terms.

The seabird population on the Blasket Islands includes puffins from April to August, nesting in burrows on the western slopes. Gannets work the deeper water off the headlands year-round, folding into near-vertical dives from height. Choughs — the red-billed, red-legged crows that Kerry is known for — follow the clifftops above the paddling routes and are close enough to hear the sound of their wings.

Why You Need a Local Guide for Sea Kayaking on the Dingle Peninsula

The Dingle Peninsula is not a forgiving place to improvise. The south shore is genuinely sheltered in many conditions, but the tidal races around Dunmore Head, the swell behaviour in the caves near Slea Head, and the currents through the Blasket Sound are local knowledge that accumulates over seasons on the same water. The difference between a cave being accessible and a cave being dangerous is sometimes a matter of two hours and a shift in swell direction — an assessment made at the launch point, not from a forecast.

A Dingle Peninsula sea kayaking guide does not simply lead you to the places on the map. They read the water ahead of you in real time, make the calls that don't appear in any forecast, and know which days the north shore is worth attempting and which days the south shore is where the interesting paddling is. They know the specific entry angle on a particular cave, the seal colony that tolerates a patient approach, and when conditions allow a crossing attempt to Great Blasket. Before you go, What to Pack for Sea Kayaking in Ireland: A Practical Kit List covers everything you should bring and what a guide will typically provide — worth reading before you book anything.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is sea kayaking on the Dingle Peninsula suitable for beginners?

The south shore between Dingle town and Slea Head is genuinely accessible for beginners in calm conditions when paddling with a guide. The sea caves and the Blasket Sound crossing are not. Most operators on the peninsula offer graded sessions — introductory paddles that use the sheltered coves near Dingle harbour, stepping up to the Slea Head headland for those with some water experience. If you've never sat in a sea kayak before, Sea Kayaking for Beginners in Ireland: What Your First Session Will Actually Feel Like will give you a realistic picture of what to expect before you commit to a booking.

When is the best time to sea kayak on the Dingle Peninsula?

May to September covers the most reliable window. June and July produce the calmest average swell and the longest light — sessions can run to eight or nine in the evening. May and September are the months that regulars return to: fewer boats on the water, better wildlife activity in both directions of the season, the same quality of experience with a fraction of the summer company. The sea caves require swell conditions that can occur year-round, and experienced paddlers find good windows in April and October on the right forecast.

Can you kayak to the Blasket Islands?

The crossing from Dunmore Head to Great Blasket is approximately three kilometres through the Blasket Sound, which has strong tidal flows. It is done regularly by guided groups when conditions are suitable. The decision is made on the day, at the water's edge — a crossing that looks marginal on paper can open up in the morning calm, and one that looked promising can close on an afternoon shift of wind. Independent paddlers without local knowledge of the sound should not attempt it. With the right guide and the right conditions, it is one of the more affecting things you can do on a kayak in Ireland.

Are there guided sea kayaking tours on the Dingle Peninsula?

Yes. Several operators run guided kayak sessions from Dingle town, ranging from half-day introductory sessions in sheltered water to full-day expeditions along the Slea Head coastline. A smaller number of guides run multi-day routes incorporating the north shore and camping. The operators who work this coastline year-round are the only reliable way to time the cave access correctly and to make a considered crossing attempt to the Blaskets.

The Dingle Peninsula rewards the effort of getting close to it. The road gives you one version — photographed, signposted, shared with everyone else who made the drive. The water gives you the version with no footpath, no car park, and often no one else in sight. For the full picture of sea kayaking across Ireland's coast, Sea Kayaking in Ireland: A Complete Guide covers every region worth considering. To find guides who paddle this peninsula in all seasons, browse our Dingle Peninsula sea kayaking guides. And if a longer paddle along the west coast is taking shape in your thinking, Multi-Day Sea Kayaking in Ireland: How to Plan a Paddle Camping Trip on the West Coast covers what's possible and what it takes to do it properly.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

What to Pack for Sea Kayaking in Ireland: A Practical Kit List

Everything you need for sea kayaking in Ireland — from dry suits to PLBs to what your guide already carries. A practical kit list for Atlantic paddling conditions.