Skellig Michael: How to Visit Ireland's Remote Hermitage Monastery

The first glimpse of Skellig Michael from the boat is unforgettable—a jagged granite peak erupting from the Atlantic, defying the ocean that has battered it for millennia. As your vessel approaches, the impossible becomes visible: stone beehive huts clinging to the upper slopes, a medieval monastery perched on a island that no sane person would choose for habitation. And yet monks lived here for six centuries, seeking God in isolation, storm, and silence.

Visiting Skellig Michael requires commitment. You can't simply drive up and walk in. The island lies 12 kilometers off County Kerry's coast, accessible only by small boat through potentially rough seas. Limited permits mean booking months in advance. The climb to the monastery—618 stone steps carved into the cliff face—demands physical fitness and a head for heights. But those who make the journey describe it as transformative: the most remarkable ancient site in Ireland, a place where human devotion and natural wildness achieve perfect harmony.

This guide, part of our comprehensive Spiritual Travel in Ireland: The Complete Guide to Sacred Sites, Pilgrimages & Ancient Monasteries — the master hub, covers everything you need to know about visiting Skellig Michael. From securing permits to surviving the boat ride, from climbing the steps to understanding the monks who called this wilderness home.

Why Skellig Michael Matters: A UNESCO World Heritage Treasure

The monks who built Skellig Michael's monastery between the sixth and eighth centuries chose deliberately. The island offered everything their spiritual practice required: total isolation, maximum difficulty, and the daily reminder of human vulnerability provided by an angry ocean. In an age when hermits sought ever-more-extreme locations, Skellig Michael represented the ultimate retreat—a place where survival itself demanded constant effort, leaving little energy for worldly temptation.

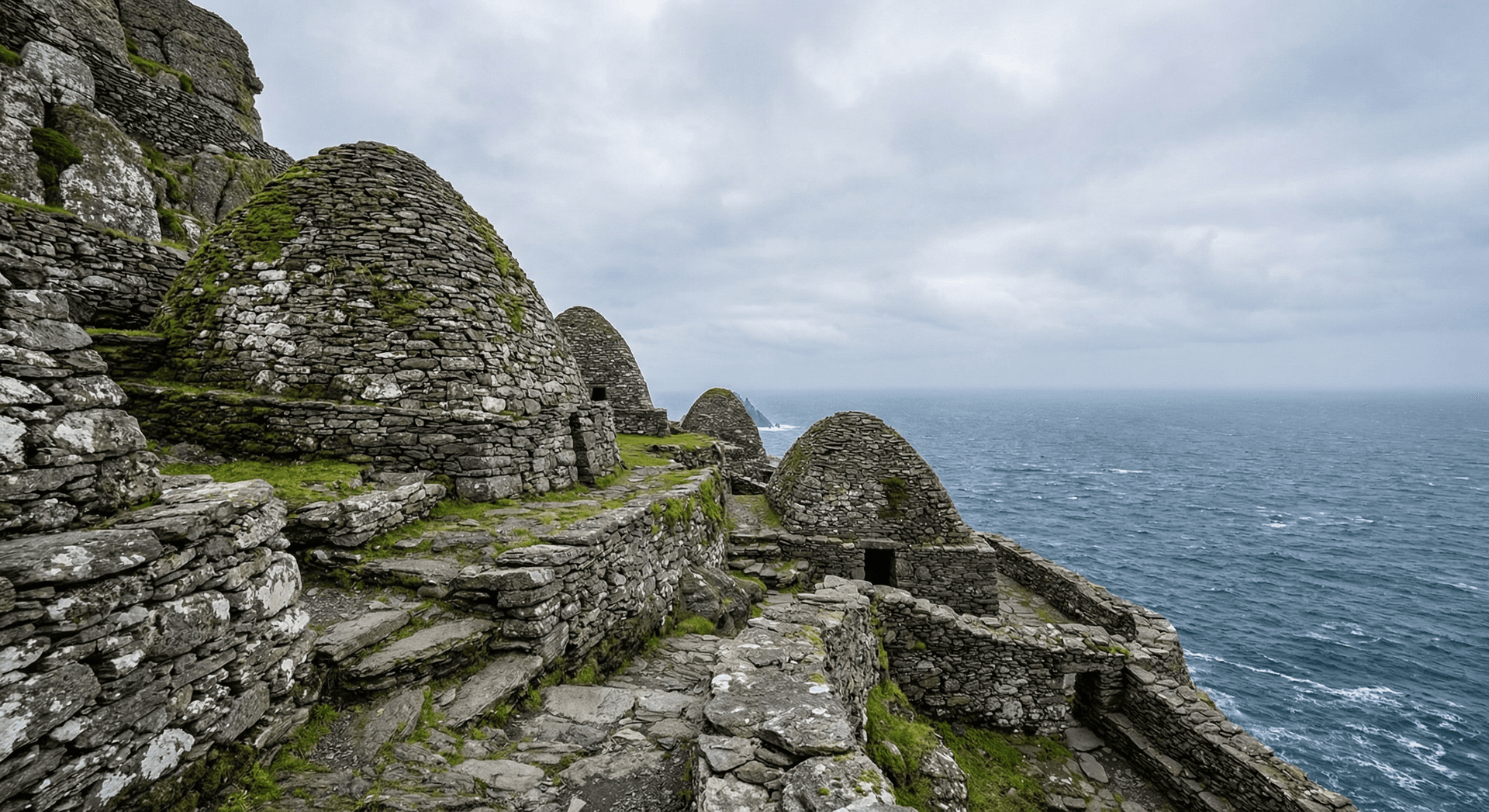

The monastery they constructed defies engineering logic. Using only dry-stone techniques—no mortar, no cement—they created beehive huts that have survived Atlantic gales for 1,400 years. The main settlement consists of six intact huts clustered around an oratory and two small churches, all positioned on a narrow terrace 180 meters above the sea. The monks farmed this improbable ground, kept livestock, and maintained a small garden. How they managed, history doesn't fully record. That they managed at all speaks to an intensity of purpose almost unimaginable today.

UNESCO recognized Skellig Michael as a World Heritage Site in 1996, citing the "exceptionally fine example of an early religious settlement deliberately sited on a pyramidal rock in the ocean." The designation protects the island from development and limits visitor numbers—necessarily, given the site's fragility and the dangers of the location.

The Star Wars connection brought Skellig Michael to global attention when the island served as filming location for The Force Awakens (2015) and The Last Jedi (2017). Luke Skywalker's hermitage was constructed among the beehive huts, using the monastery's otherworldly atmosphere to suggest a galaxy far, far away. The filming sparked controversy—conservationists worried about damage to the ancient site—but also created unprecedented interest in this remote Irish treasure. Today, visitors include both spiritual pilgrims and Star Wars fans, often finding the island speaks to both constituencies in unexpected ways.

Planning Your Visit: Permits, Booking & Timing

Skellig Michael isn't a destination for spontaneous travelers. Strict visitor limits—180 people per day—mean advance planning is essential. Here's how to secure your place on one of Ireland's most sought-after experiences.

Booking the boat:

Only licensed operators may land visitors on Skellig Michael, and just 15 boats hold permits. The season runs from mid-May through late September, weather permitting. Boats depart from three Kerry harbors:

- Portmagee (most popular, closest crossing at 1.5 hours)

- Ballinskelligs (2-hour crossing, smaller boats)

- Caherdaniel (2.5-hour crossing, limited departures)

Book at least three months in advance for July and August. Some operators open bookings in January for the coming season. Prices range from €100-150 per person, including the landing fee. Don't book accommodation until you have confirmed boat tickets—the crossing is weather-dependent, and cancellations are common.

Weather contingencies:

The Atlantic dictates whether boats sail. Skellig Michael sits where the Gulf Stream meets cold northern currents, creating unpredictable conditions. Operators monitor forecasts constantly and make go/no-go decisions at 6 AM on sailing days. If your trip is cancelled, most operators offer rescheduling or refunds, but flexibility in your itinerary is essential.

The crossing itself can be rough. Even calm mornings at the harbor can become challenging once you clear the headlands. If you're prone to seasickness, take medication before boarding—the journey is too spectacular to spend with your head in a bucket.

Physical requirements:

The island landing requires agility. Boats tie up at concrete slips at the island's east side, but swells mean you must time your step onto the dock carefully. The operator's crew will assist, but this isn't suitable for anyone with mobility limitations.

Once ashore, the monastery climb awaits: 618 uneven stone steps ascending steeply to the settlement. There are no handrails, no benches, no shade. The return descent is equally demanding on knees and concentration. You need reasonable fitness, sturdy boots, and comfort with heights. Several people are injured annually—usually by rushing or poor footwear.

What to bring:

- Layers and waterproofs: The island creates its own weather. Even warm mainland mornings can be cold and windy here.

- Sturdy hiking boots: Essential for the stone steps. Sandals or runners lead to slips.

- Water and snacks: No facilities exist on the island. Bring more than you think you need.

- Sun protection: No shade means sunburn happens fast on clear days.

- Camera, carefully: The views demand documentation, but protect your equipment from salt spray and sudden gusts.

The Boat Journey: Crossing to the Edge of the World

The 12-kilometer crossing to Skellig Michael takes 90 minutes to 2.5 hours depending on your departure point and sea conditions. Most visitors find this journey as memorable as the island itself—a passage through waters teeming with wildlife, past seabird colonies, toward a destination that looks increasingly improbable as you approach.

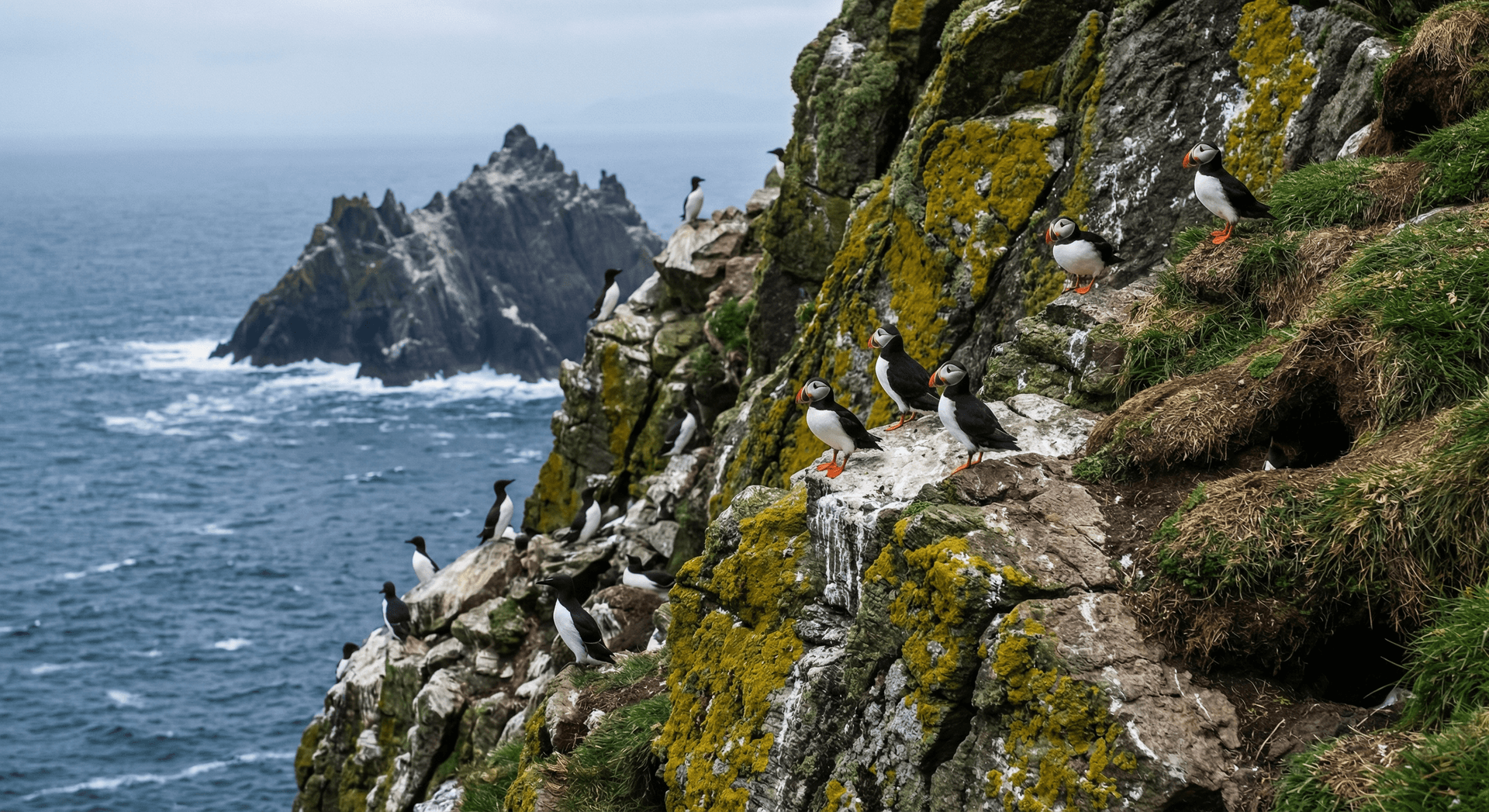

Wildlife encounters are virtually guaranteed. Puffins nest on the Little Skellig (the smaller neighboring island) from April through July, and thousands cover the rocky slopes—comical, colorful, utterly unafraid of boats. Gannets, guillemots, and razorbills carpet the sea cliffs. Dolphins and basking sharks sometimes accompany vessels. The Skelligs represent one of Europe's most important seabird breeding sites, and the boat passage offers wildlife watching comparable to dedicated nature cruises.

The approach to Skellig Michael reveals why monks chose this location. The island rises dramatically from the sea, a pyramid of naked rock that seems to repel life itself. Yet as you draw closer, the beehive huts become visible—tiny stone structures improbably positioned on the upper slopes. The contrast between the barren rock and these evidence of human habitation creates the first of many moments of wonder.

Boat operators typically circle the island before landing, offering views of the monastery from below, the hermit's cell on the south peak, and the lighthouse complex on the east side. This circumnavigation also assesses landing conditions—the skipper needs to judge whether the swells permit safe disembarkation at the concrete slips.

The Climb: 618 Steps to the Monastery

Landing on Skellig Michael's east side, you face immediate choice: climb or not. There's no shame in staying at the lower level—the views from the landing area are spectacular, and the seabird colonies here are accessible without ascent. But the monastery rewards those who make the climb with one of Ireland's most profound experiences.

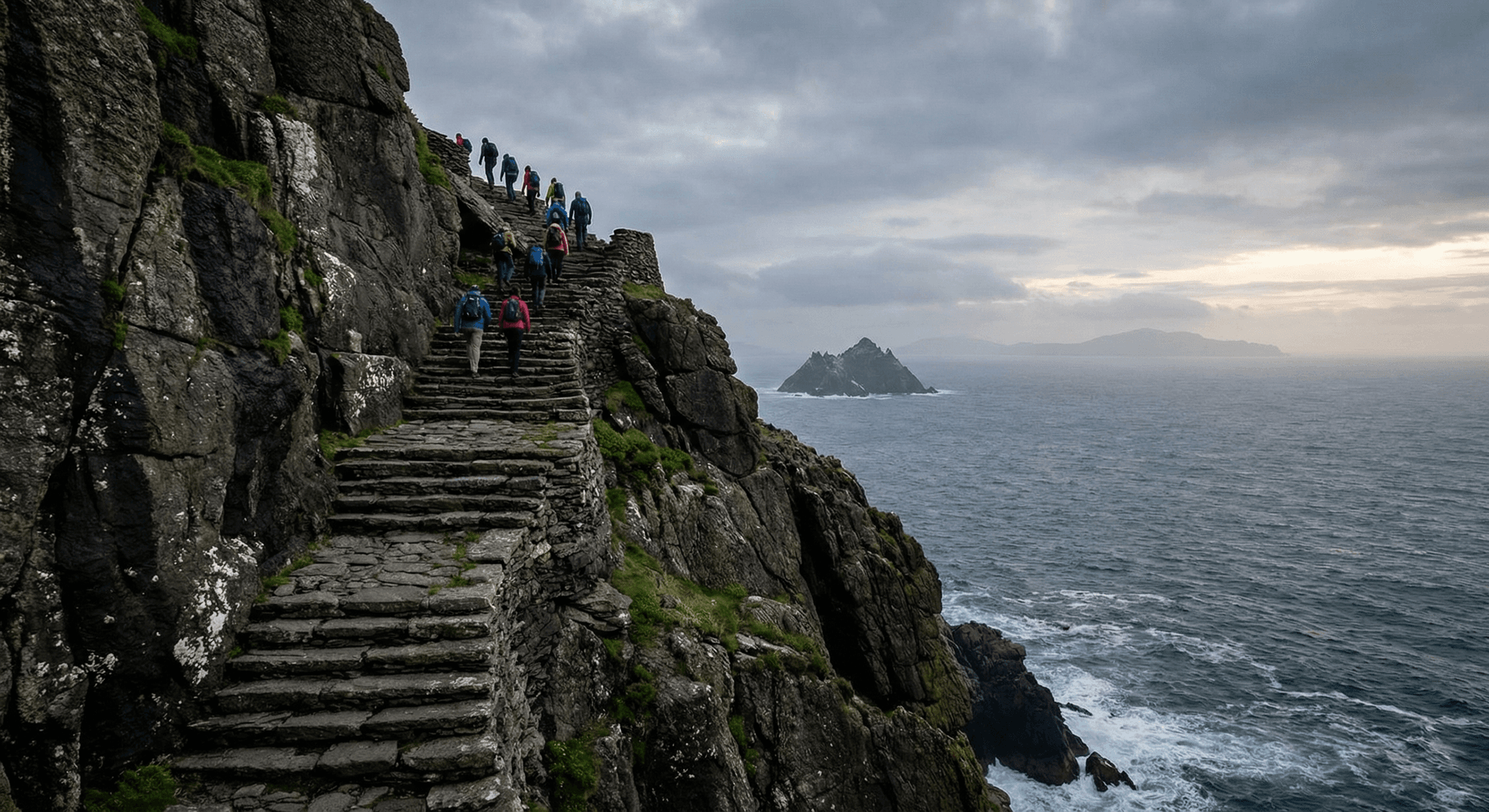

The stone steps are original—laid by monks over a thousand years ago, maintained by Office of Public Works today. They're uneven, sometimes loose, occasionally treacherous when wet. The climb takes 30-45 minutes for fit hikers, longer for others. Rushing invites disaster; several annual injuries result from haste.

The path offers no shade and no escape. Once you commit, you climb until you reach the monastery or turn back. The steps switchback across the island's south face, offering increasingly dramatic views of Little Skellig, the Kerry coast, and the open Atlantic. Rest stops are unofficial—just places where the gradient briefly eases. Most climbers find the psychological challenge exceeds the physical; the exposure to wind and height creates vulnerability that the monks surely experienced as spiritual opportunity.

Near the top, the monastery appears suddenly. You round a corner, and there they are: six beehive huts clustered together, impossibly intact after fourteen centuries. The sense of arrival—of having earned access to something remarkable—makes the climb feel not like effort but like pilgrimage.

The Monastic Settlement: Life on the Edge

The monastery terrace measures perhaps 50 meters across—a level area carved from the slope by monks who understood that habitation here required flat ground. Within this limited space, they created everything necessary for communal religious life.

The beehive huts represent the site's most distinctive feature. Built without mortar using corbelling techniques—each stone slightly overlapping the one below until the walls meet at the top—these structures have survived Atlantic storms since the early medieval period. Six huts remain intact, their doorways low (medieval people were smaller), their interiors dark and womb-like. One can enter most huts today, crouching through the entrance to stand inside these ancient spaces. The acoustics are remarkable; monks' chanting would have resonated through the stone.

The oratory served as the community's church—a tiny rectangular building with stone walls and (originally) a timber roof. Services here followed the demanding monastic hours: Matins at midnight, Lauds at dawn, continuing through the day. The church's diminutive size suggests a small community, perhaps six to twelve monks at any time.

The monks' garden occupies a small level area where soil accumulated. Archaeological investigation revealed evidence of cereal cultivation—oats and barley grown in this impossible location, perhaps supplemented by vegetables and herbs. The monks also kept livestock; sheep and goats provided milk, cheese, and wool. How they prevented animals from tumbling off the cliffs remains unclear.

The south peak hermitage represents an even more extreme expression of solitude. A tiny beehive hut and oratory perch on the island's highest point, accessible only by a perilous climb. Legend attributes this retreat to Saint Michael, though archaeology suggests later medieval construction. Only experienced climbers should attempt the ascent; the Office of Public Works restricts access for safety reasons.

Star Wars: Hollywood Discovers the Skelligs

In 2014, Disney location scouts seeking "the most remote and unearthly place possible" for Luke Skywalker's hideaway discovered what Irish monks had known for centuries. Skellig Michael's otherworldly atmosphere—stone structures against barren rock, surrounded by endless ocean—provided perfect backdrop for The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi.

The production constructed minimal sets—just a doorway and steps among the beehive huts, plus some digitally-added structures in post-production. The island itself provided the magic. Mark Hamill spent weeks filming here, describing the experience as "profoundly moving" despite the discomfort of location work.

For visitors, the Star Wars connection adds unexpected layers. The "Jedi steps"—the stone staircase built for the films—remain, though purists debate whether they enhance or detract from the ancient site. Props and sets were removed after filming, but the association persists. Some visitors arrive seeking spiritual connection with early Christianity; others seek connection with a galaxy far, far away. Most find the island transcends both frameworks.

The filming brought welcome resources for conservation but also raised concerns about managing increased visitor numbers. UNESCO closely monitors impacts, and Irish authorities limit daily visitors precisely to prevent the site becoming overwhelmed. The Star Wars pilgrims and the religious pilgrims must share limited space—a microcosm of broader tensions between tourism and preservation.

Practical Tips for a Successful Visit

Physical preparation matters. If you're not regularly walking hills, train before your visit. The 618 steps demand leg strength and cardiovascular fitness. Practice walking on uneven surfaces; the monastery path offers no smooth pavement.

Weather watching is essential. Check forecasts obsessively in the days before your trip. If operators cancel due to conditions, accept their judgment—they know these waters better than you ever will.

Time your climb to avoid crowds. Early morning boats (8-9 AM) reach the island before most visitors arrive. The monastery feels very different with ten people versus fifty. Conversely, afternoon light offers better photography, though afternoon weather is less reliable.

Respect the site's fragility. Don't climb on walls, don't move stones, don't take "souvenirs." The beehive huts survived fourteen centuries; modern visitors should ensure they survive fourteen more.

Mental preparation helps. This isn't a comfortable day out. You may be cold, wet, seasick, exhausted. But discomfort is part of the experience—the monks chose this location precisely because comfort wasn't the point. Embrace the difficulty as they did.

Where to Stay: Exploring the Ring of Kerry

Most Skellig Michael visitors base themselves on the Ring of Kerry, the scenic driving route that passes through some of Ireland's most spectacular coastal landscapes. Several towns offer accommodation within easy reach of the boat departure points.

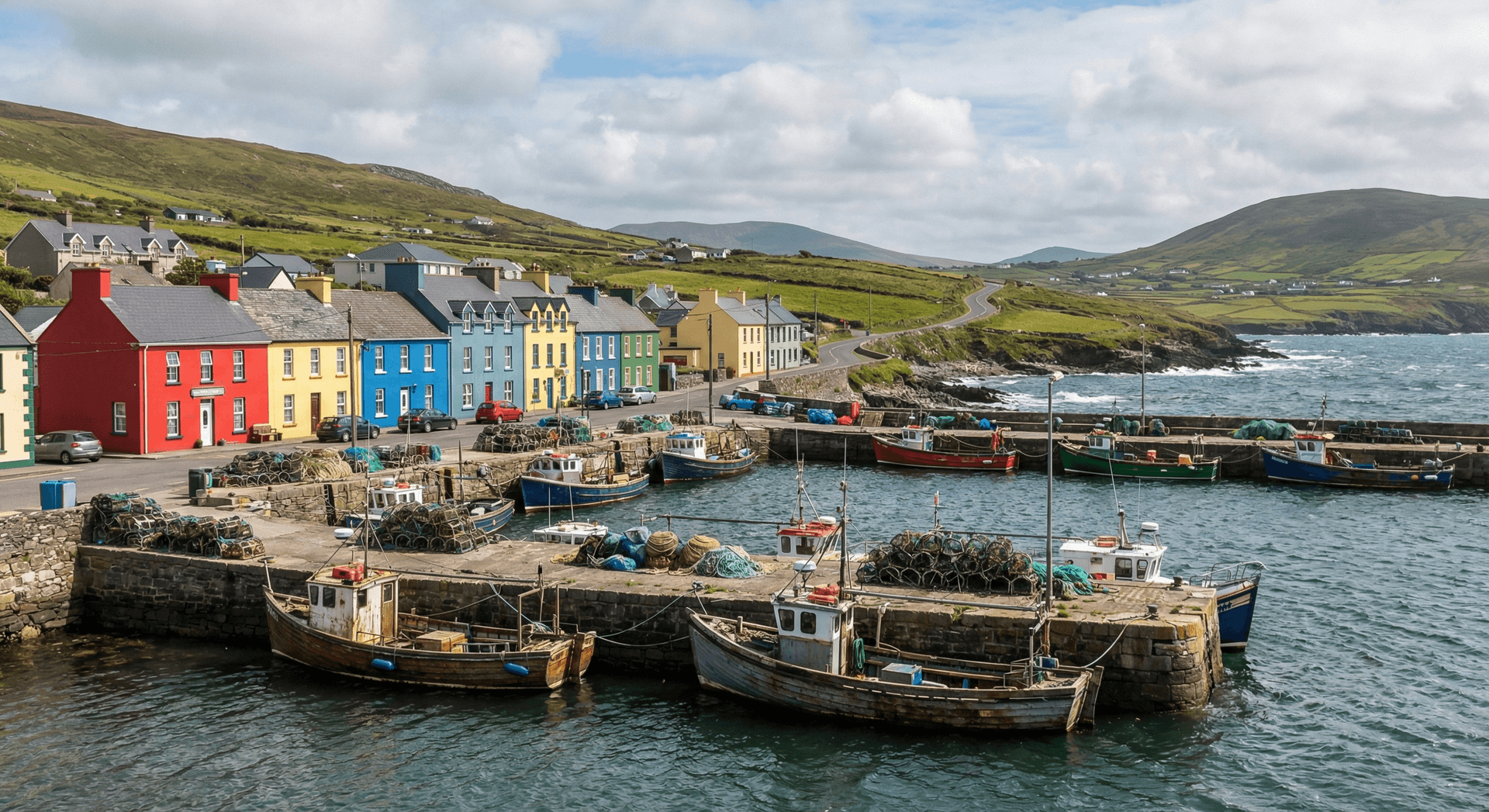

Portmagee sits closest to the Skelligs, a tiny fishing village with a bridge connection to Valentia Island. The village offers several guesthouses and B&Bs, plus the famous Bridge Bar for post-trip celebration. Staying here means minimal driving on boat day—essential given early departure times.

Waterville provides more upscale options, including the Butler Arms Hotel (a favorite of Charlie Chaplin's). The town sits on the Ring of Kerry with beach access and golf courses, offering activities if your Skellig trip gets weather-cancelled.

Ballinskelligs combines beach and history, with the ruins of a medieval monastery and castle complementing the Skellig experience. Several excellent restaurants and comfortable guesthouses make this a pleasant base.

Killarney offers the widest range of accommodation but requires an hour's drive to the boat departure points. Stay here if you're exploring Kerry more broadly; choose somewhere closer if Skellig Michael is your primary focus.

Final Thoughts: The Gift of Skellig Michael

Leaving Skellig Michael—descending the steps, crossing the water, returning to mainland concerns—creates strange melancholy. The island's intensity, its improbability, its profound silence (when tourists aren't shouting) leaves marks on visitors that persist long after the boat docks.

Whether you come for spiritual reasons, Star Wars pilgrimage, or simple curiosity, Skellig Michael offers something increasingly rare: genuine encounter with the past. These stones were laid by hands 1,400 years ago. These huts sheltered monks who believed that isolation brought them closer to God. The Atlantic that surrounds you is the same ocean they watched, prayed beside, sometimes drowned in.

The modern world intrudes even here—booking systems, safety regulations, film crews. But the core experience remains what it was for medieval pilgrims: effort, exposure, and finally arrival at a place that challenges everything comfortable about contemporary life. You can't visit Skellig Michael casually. The island demands too much for that.

Those demands are the gift. In an age of easy access and instant gratification, Skellig Michael requires commitment, planning, physical effort, and acceptance of discomfort. The reward isn't comfort—it's meaning. Standing among beehive huts built by monks who understood something about devotion that we have forgotten, watching gannets dive into an ocean that hasn't changed in millennia, you touch something ancient and true.

Book early. Prepare well. Accept that weather may defeat you. But if you reach Skellig Michael, climb those steps, and sit among the stone huts looking out at the Atlantic, you'll understand why monks chose this improbable place—and why, fifteen centuries later, it still calls to those seeking something beyond the ordinary.

For a complete overview of Ireland’s most important ancient and spiritual locations, see our master guide to Sacred Ireland.

Related Sacred Sites

For more dramatic cliff-side archaeology, see our guide to the forts of the Aran Islands.

The profound sense of isolation is a theme it shares with the demanding pilgrimage to Lough Derg.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.