The Aran Islands (Inis Mór): Dun Aonghasa & The Seven Churches

The Aran Islands rise from the Atlantic thirty miles off Ireland's west coast like a fragment of the ancient world that time forgot. Three limestone outcrops — Inis Mór, Inis Meáin, and Inis Oírr — where Gaelic is still the first language of daily life, where fields are divided by stone walls built by hand over generations, and where the ruins of monastic settlements stand as they have for a thousand years, buffeted by Atlantic gales and salt spray.

Inis Mór, the largest island, is the one most visitors experience — and with good reason. This small patch of limestone, barely twelve miles long, contains some of the most spectacular archaeological sites in Europe. The stone fort of Dún Aonghasa perches on a three-hundred-foot cliff, its walls following the edge of the precipice in defiance of logic and gravity. The Seven Churches, a monastic settlement founded in the eighth century, preserves the ruins of churches, crosses, and domestic buildings that paint a vivid picture of medieval island life. Ancient pagan forts, early Christian oratories, and the distinctive booley huts of the transhumant farmers who once moved their cattle between summer and winter pastures — all of it is here, exposed to the Atlantic winds.

This guide covers everything you need to know about visiting Inis Mór as a sacred destination. We will walk you through Dún Aonghasa and the Seven Churches, explain the island's unique spiritual landscape, and share practical tips that will make your visit far more rewarding than the typical day-trip sprint. The Aran Islands are not a place for rushing. They reward slow exploration, bad-weather endurance, and the willingness to get lost among the stone walls. This is part of our comprehensive guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

Getting to Inis Mór: Ferry or Flight to Another World

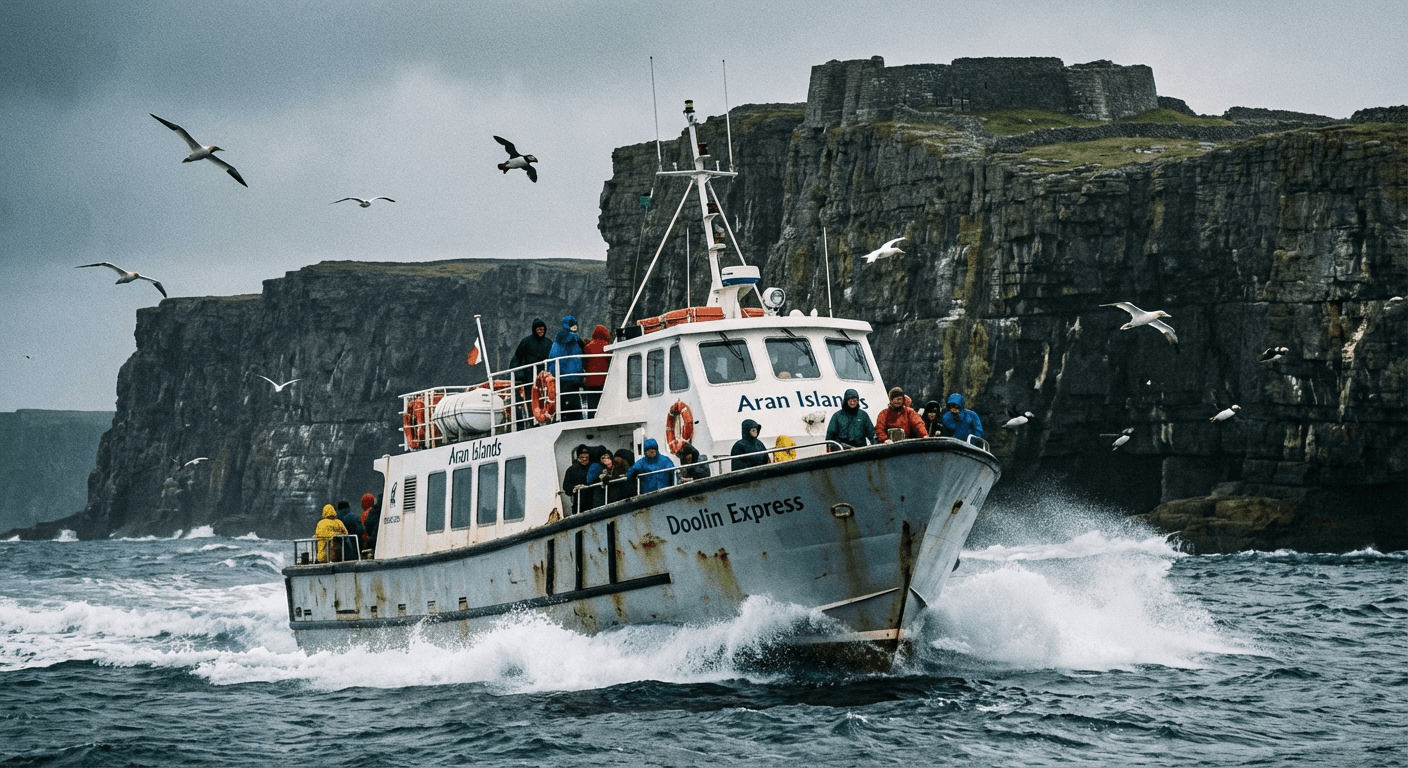

Inis Mór is accessible only by sea or air — and that isolation is precisely what has preserved its culture and character. Two ferry companies operate from Rossaveal, a small harbour forty minutes west of Galway city. The crossing takes about forty minutes in good weather, longer when the Atlantic is rough. In summer, there are multiple sailings daily. In winter, service is reduced and weather-dependent.

The ferries are substantial vessels, capable of handling moderate seas, but the crossing can still be uncomfortable for those prone to seasickness. If you are susceptible, take medication before boarding and stay on deck where you can see the horizon. The reward is worth the discomfort: the approach to Inis Mór, with the cliffs of Dún Aonghasa visible from miles away, is one of the great arrivals in Irish travel.

Alternatively, Aer Arann Islands operates flights from Connemara Airport (twenty minutes west of Galway) to Inis Mór. The eight-minute flight in a small twin-prop aircraft offers spectacular views of the Galway coast, the Burren, and the islands themselves. It is more expensive than the ferry but saves time and avoids seasickness entirely.

Island Transport

Inis Mór has no public transport to speak of. Your options are walking (the island is small enough to explore on foot, though distances are deceptive), bicycle rental (ideal for seeing the island), minibus tours (efficient but rushed), or pony and trap (traditional but increasingly rare). For exploring the sacred sites properly, walking or cycling is best. You want the flexibility to stop where you like, to stay at a site until the tour buses leave, to follow the side paths that lead to hidden ruins.

Dún Aonghasa: The Fort at the Edge of the World

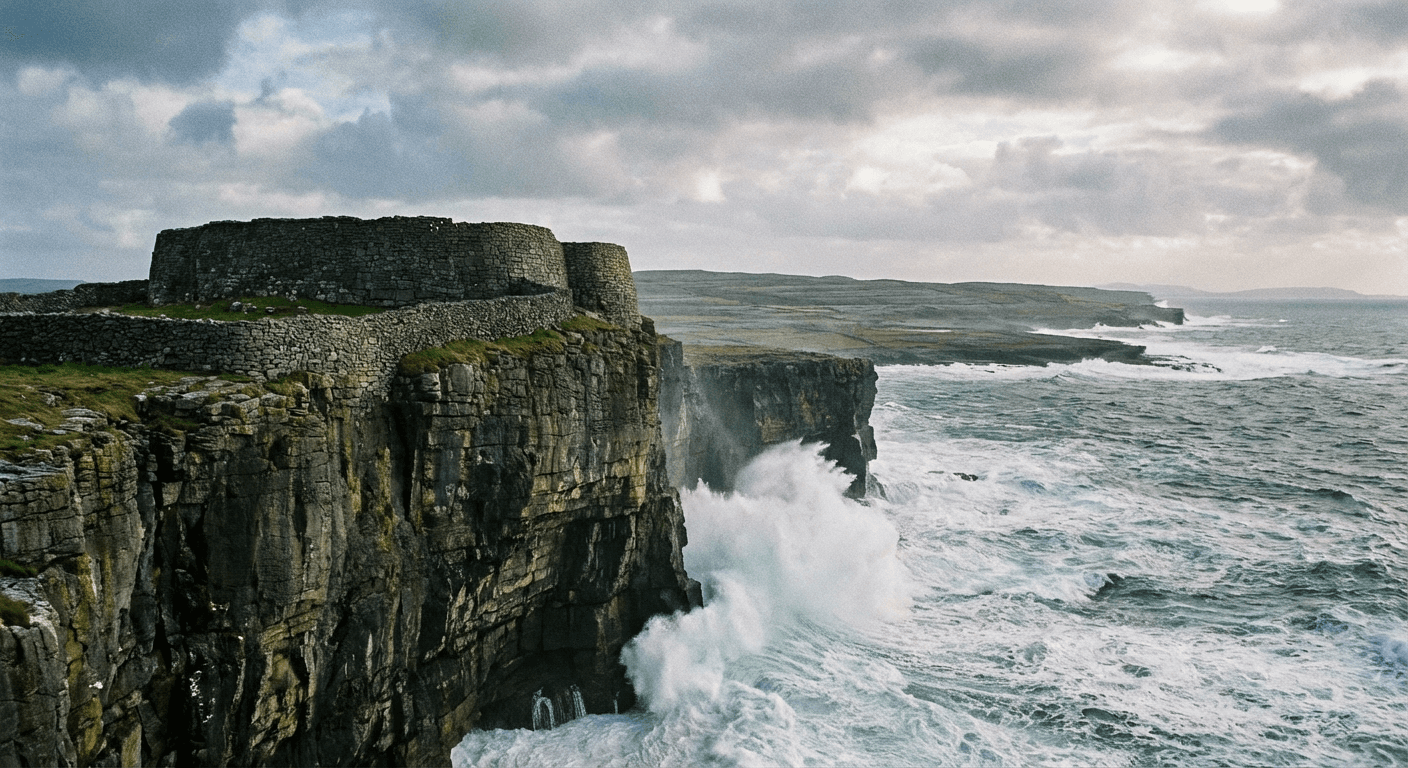

Dún Aonghasa is the reason most people come to Inis Mór — and it does not disappoint. This massive stone fort, built sometime between 1000 BC and 500 AD, occupies a spectacular position on the island's southern coast. Three concentric stone walls enclose a semicircular area that ends at a three-hundred-foot cliff dropping sheer into the Atlantic. The fourth side needs no wall. The ocean provides the defence.

The scale of Dún Aonghasa is hard to appreciate until you walk the walls. The inner enclosure, called the citadel, contains a chevaux-de-frise — a band of upright stone slabs set in the ground to impede cavalry or rushing infantry. This is the only surviving example in Ireland, and it suggests a sophistication of military engineering that challenges assumptions about primitive Iron Age societies.

Who built Dún Aonghasa? Legend attributes it to Aonghas, a mythical king, but the truth is lost in prehistory. The fort was clearly a centre of power — a chieftain's stronghold, a refuge in times of war, a statement of dominance over the surrounding territory. Its position, with visibility for miles along the coast and across to the mainland, made it virtually impregnable to assault from the landward side.

Visiting Dún Aonghasa

The fort is managed by the Office of Public Works. There is a small visitor centre near the entrance with exhibitions on the site's archaeology and history. From there, it is a fifteen-minute walk uphill to the fort itself — the path is steep and uneven, not suitable for those with mobility issues.

What to look for: the chevaux-de-frise in the inner enclosure — imagine trying to charge across that field of stone blades. The views from the cliff edge — on clear days you can see the Cliffs of Moher, the Burren, and the mountains of Connemara. The stonework of the walls, built without mortar, using the natural fractures of the limestone. The rock platform beyond the outer wall, possibly used for ceremonial purposes.

Safety warning: The cliff edge is unfenced. People have died here. Stay well back from the edge, especially in windy conditions when sudden gusts can destabilise even careful walkers. Do not attempt selfies at the cliff edge — the risk is not worth any photograph.

The Seven Churches: Monastic Life on the Atlantic Edge

If Dún Aonghasa represents the pagan, warrior past of the Aran Islands, the Seven Churches represent their Christian future. This monastic settlement, founded in the eighth century and active for six hundred years, was one of the most important religious centres in western Ireland. Pilgrims came from across Europe to study, to pray, and to be buried in sacred ground.

The name Seven Churches is misleading. There were never exactly seven churches here — the name comes from the Irish Na Seacht dTeampaill, which might refer to seven distinct religious buildings or simply mean the many churches. What remains is a complex of ruins spread across a sheltered hollow: two substantial churches, several smaller oratories, domestic buildings, crosses, and grave slabs.

Teampall Bhreacain (Brecan's Church) is the largest and oldest structure, founded by Brecan, a saint about whom little is known except that he gives his name to the site. The church is a simple rectangular building with an added chancel, typical of early Irish monastic architecture. Inside, the floor is paved with grave slabs, many carved with the distinctive Aran cross — a simple Latin cross with splayed arms.

Teampall an Phoill (the Church of the Hollow) is smaller but better preserved. It features a fine lintelled doorway and several carved stones incorporated into the walls. The hollow that gives the church its name may have been a pre-Christian sacred site, later baptised by the monks.

The crosses and grave slabs scattered around the site are the real treasure. Some date to the eighth and ninth centuries, carved by craftsmen working in a distinctive local style. Look for the cross with the crucifixion scene — crude but moving, Christ on the cross with two figures standing below. The inscription is worn, but the image speaks across twelve centuries.

The pilgrims' path leads from the Seven Churches to a holy well dedicated to Brecan, about half a kilometre away. The well is still visited by local people, who leave offerings and prayers. The combination of church, well, and pilgrimage route creates a complete sacred landscape — the kind of integrated spiritual geography that characterises Sacred Ireland at its best.

The Burren Connection: Landscape as Sacred Text

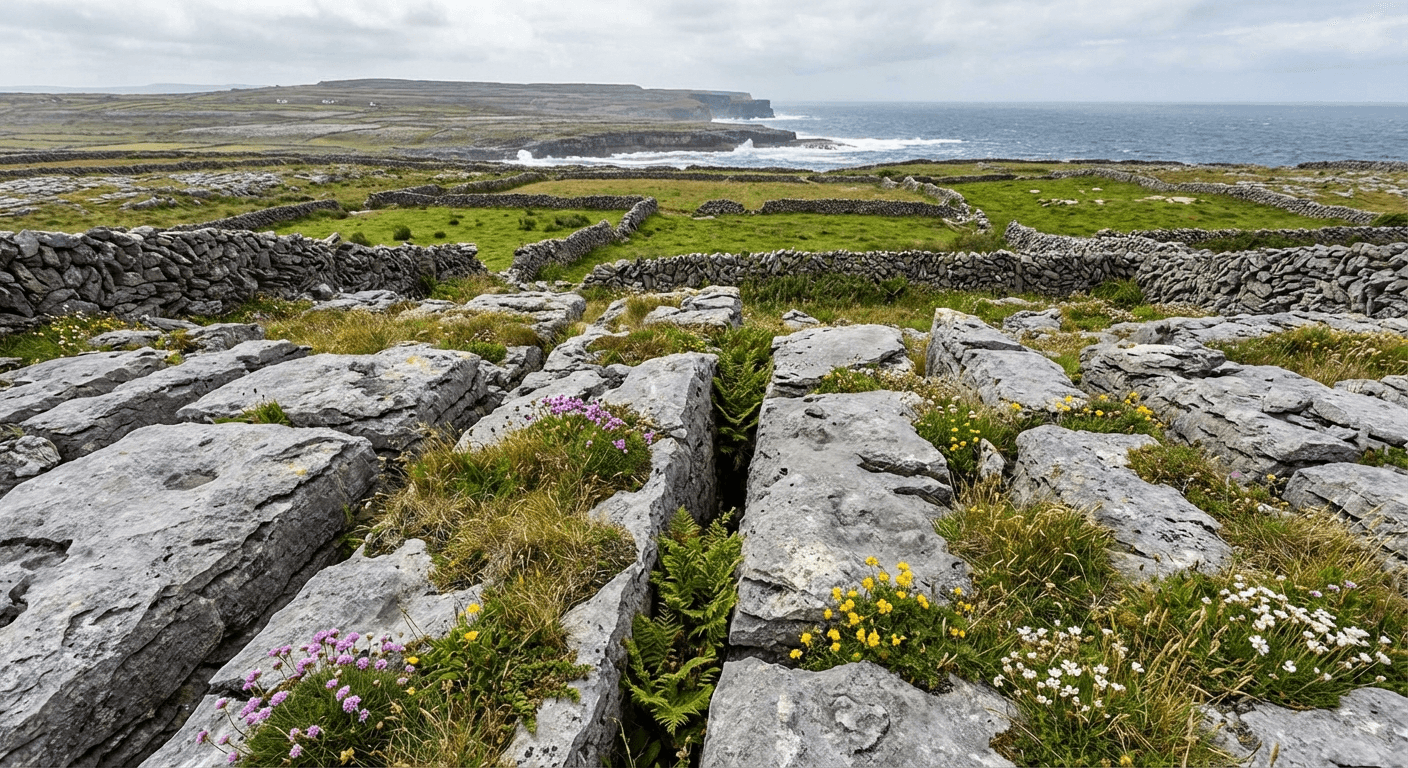

Inis Mór is geologically part of the Burren, that unique karst landscape of limestone pavement that stretches across County Clare and into Galway. The same forces that created the Burren's clints and grikes — the blocks and fissures of the limestone pavement — shaped Inis Mór. The result is a landscape that looks like nowhere else in Ireland.

For the early inhabitants, this landscape was not barren or hostile. It was sacred. The limestone provided building material for the massive forts and churches. The thin soil, carefully managed with seaweed and sand, produced surprisingly good crops. The countless fissures in the rock provided shelter for livestock. And the scarcity of resources created a culture of ingenuity and cooperation that persists today.

The stone walls of Inis Mór are the most visible expression of this culture. There are over 1,500 kilometres of wall on this small island — enough to stretch from Dublin to Bucharest. They were built by hand, stone by stone, over centuries, to divide the precious arable land into manageable strips. The patterns they create — straight lines, gentle curves, intricate networks — are as much works of art as agricultural infrastructure.

Walking among these walls, you understand something about the relationship between people and landscape in Sacred Ireland. The land was not merely property to be exploited. It was a gift to be stewarded, a text to be read, a presence to be respected. The forts, the churches, the walls, the fields — all of it speaks of a people who understood themselves as part of something larger than their individual lives.

Other Sacred Sites on Inis Mór

Beyond Dún Aonghasa and the Seven Churches, Inis Mór contains numerous other sites worth seeking out. You will not find them in the guidebooks, and there are no signs pointing the way. But that is precisely the point — part of the joy of Inis Mór is discovery, stumbling across ancient stones in a field of cows, wondering who built them and why.

Dún Eochla is a smaller stone fort near the centre of the island, less dramatic than Dún Aonghasa but more accessible and usually deserted. The views from the walls encompass the whole island — a perfect orientation point. Dún Dúchathair (the Black Fort) sits on the southeast coast, another cliff-edge fortification with a chevaux-de-frise. It is harder to reach than Dún Aonghasa, requiring a walk across rough terrain, but the solitude rewards the effort.

Teampall Chiaráin is a small early Christian oratory near the island's eastern end. It is dedicated to Saint Ciarán — possibly the same saint who founded Clonmacnoise — though the connection is uncertain. The building is simple, rectangular, with a lintelled doorway that still retains its original stone.

The Worm Hole (Poll na bPéist) is a natural feature rather than a sacred site, but it has acquired semi-mythical status. A rectangular blowhole carved by the sea into the limestone, it fills and empties with the waves. Dangerous to approach at high tide or in rough seas, but extraordinary to witness. The lighthouse at Eoghanacht marks the island's southern tip. Built in the nineteenth century, it is not ancient, but the walk to reach it passes through some of the island's most atmospheric landscape.

Practical Tips for Visiting Inis Mór

When to Visit

The Aran Islands are spectacular in any weather, but the experience varies dramatically by season. Summer (June-August) offers the best chance of calm seas and warm days, but also the most crowds. May and September are ideal — good weather, fewer visitors, lower prices. Winter can be magical if you do not mind rough seas, limited ferry service, and the possibility of being storm-bound for an extra day or two.

What to Bring

Waterproof everything — jacket, trousers, boots. The Atlantic weather changes rapidly. Warm layers, even in summer. The wind is constant and cold. Sun protection — the limestone reflects UV, and there is no shade. Sturdy walking boots for the rough, uneven terrain. Cash — not all businesses accept cards, and there is only one ATM on the island. A sense of flexibility — ferries get cancelled, plans change.

Where to Stay and Eat

Inis Mór has accommodation ranging from hostels to boutique hotels. For a sacred sites visit, consider staying in or near Kilronan (the main village) for convenience, or in one of the smaller settlements for atmosphere. Bed and breakfasts offer the best combination of comfort and local knowledge. The island has several good pubs and restaurants. Try the local specialities: Aran lamb (the seaweed diet gives the meat a distinctive flavour), fresh seafood, and brown bread baked in the traditional style.

Why a Walking Guide Transforms Your Visit

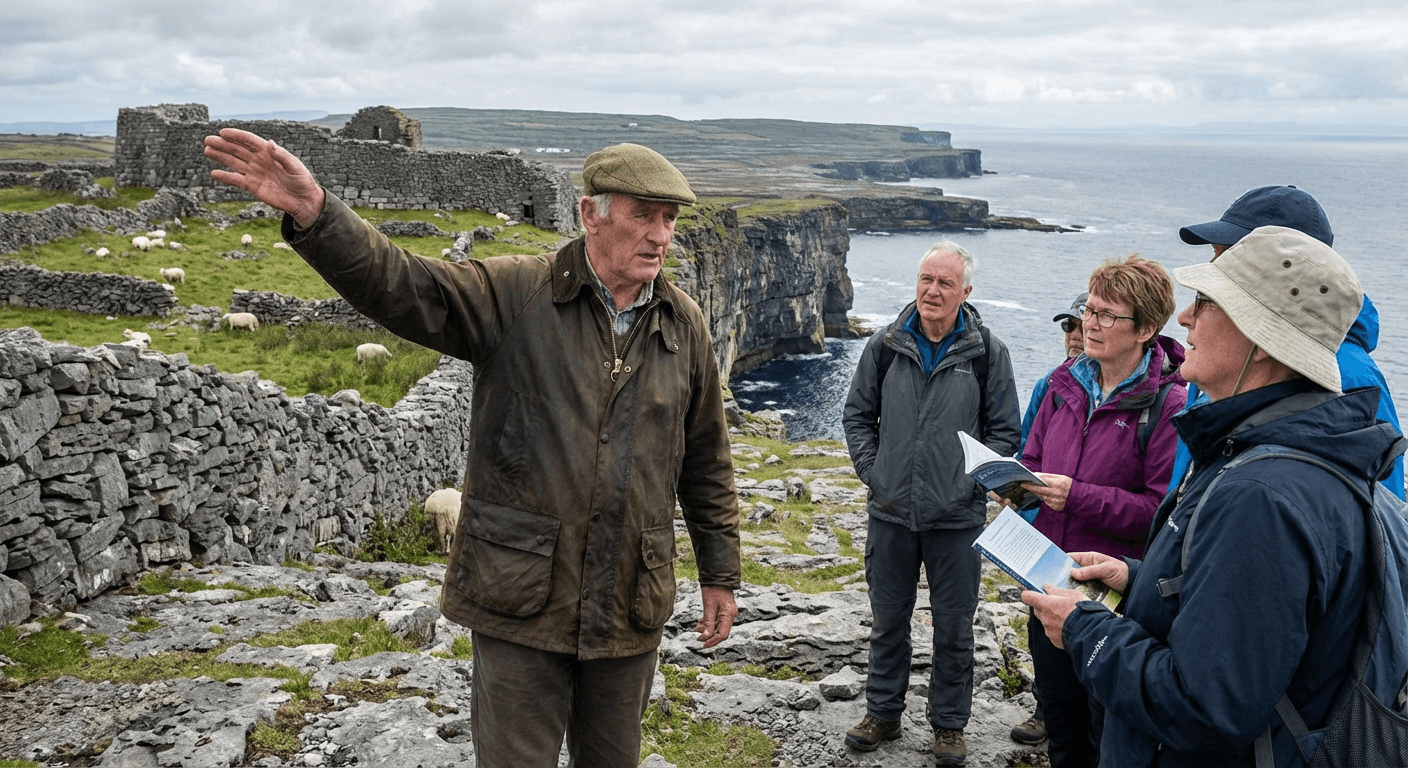

You can explore Inis Mór on your own. Many do, clutching their guidebooks and OS maps, squinting at ruins and wondering what they are looking at. You will enjoy it. The landscape is magnificent regardless.

But here is what the guidebooks will not tell you: the context that transforms stones into stories. A Walking Guide who knows Inis Mór can show you the subtle features that reveal the island's history — the different styles of wall building that indicate different periods, the faint traces of lazybed cultivation that show where potatoes were grown before the Famine, the alignment of the churches that reflects medieval beliefs about sacred geography.

They can take you to sites not on the tourist map — the holy well hidden behind a farmyard, the cross-slab incorporated into a modern field wall, the booley hut where islanders once summered their cattle. They can introduce you to Irish-speaking locals who might share stories about the sites, about patterns and pilgrimages, about the island's recent past and deep history.

More importantly, they provide safety. The cliff edges at Dún Aonghasa and other sites are genuinely dangerous. A guide knows where to walk, where to avoid, how to read the weather signs that precede Atlantic storms. They carry first aid kits and know the location of the island's defibrillators. In an emergency, they know who to call and how to get help quickly.

Conclusion

The Aran Islands offer something increasingly rare in Irish tourism: authenticity. This is not a reconstructed heritage site or a sanitised visitor experience. It is a living community, speaking its ancestral language, maintaining its ancestral customs, farming the same fields that have been cultivated for thousands of years.

The sacred sites — Dún Aonghasa, the Seven Churches, the countless lesser ruins — are part of this living tradition, not separate from it. They are maintained by the Office of Public Works, yes, but they belong to the islanders, whose ancestors built them, whose stories explain them, whose daily lives continue around them.

Visit with respect. Learn a few words of Irish — Dia dhuit (God be with you) is the traditional greeting. Buy your souvenirs from local craftspeople, not the mainland shops that ship identical goods to every tourist destination. Stay overnight if you can — the island has a different quality when the day-trippers leave and the silence of the Atlantic night descends.

For more on Ireland's sacred islands and monastic sites, see our complete guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub. And do not miss our guides to Skellig Michael, Clonmacnoise, and the Rock of Cashel for more extraordinary sacred destinations.

For a complete overview of Ireland’s most important ancient and spiritual locations, see our master guide to Sacred Ireland.

Related Sacred Sites

The dramatic cliffside location of Dún Aonghasa brings to mind the similarly precarious monastic outpost of Skellig Michael.

The stone forts here are part of the same ancient story as the passage tombs of Newgrange and Knowth.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.