The Rock of Cashel: St. Patrick's Rock & The Hore Abbey Ruin

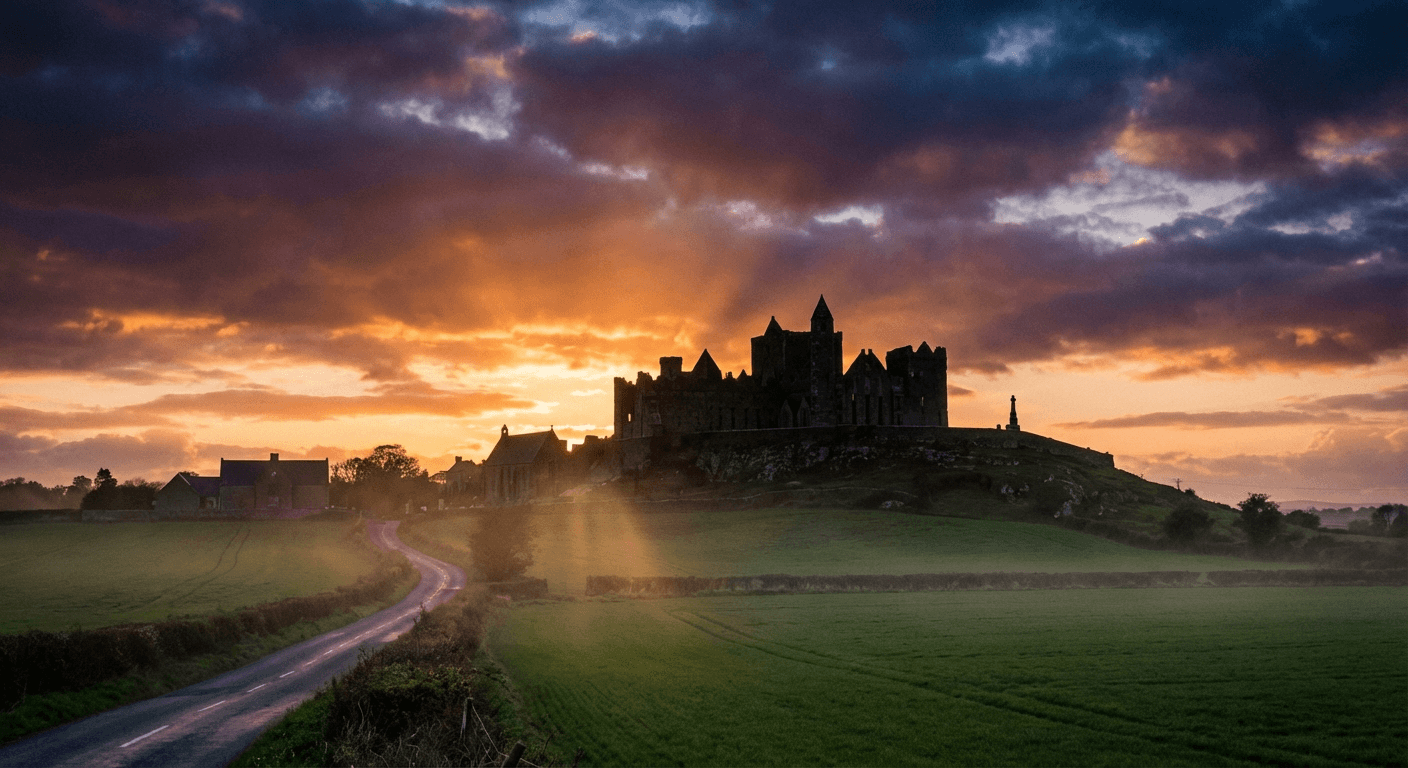

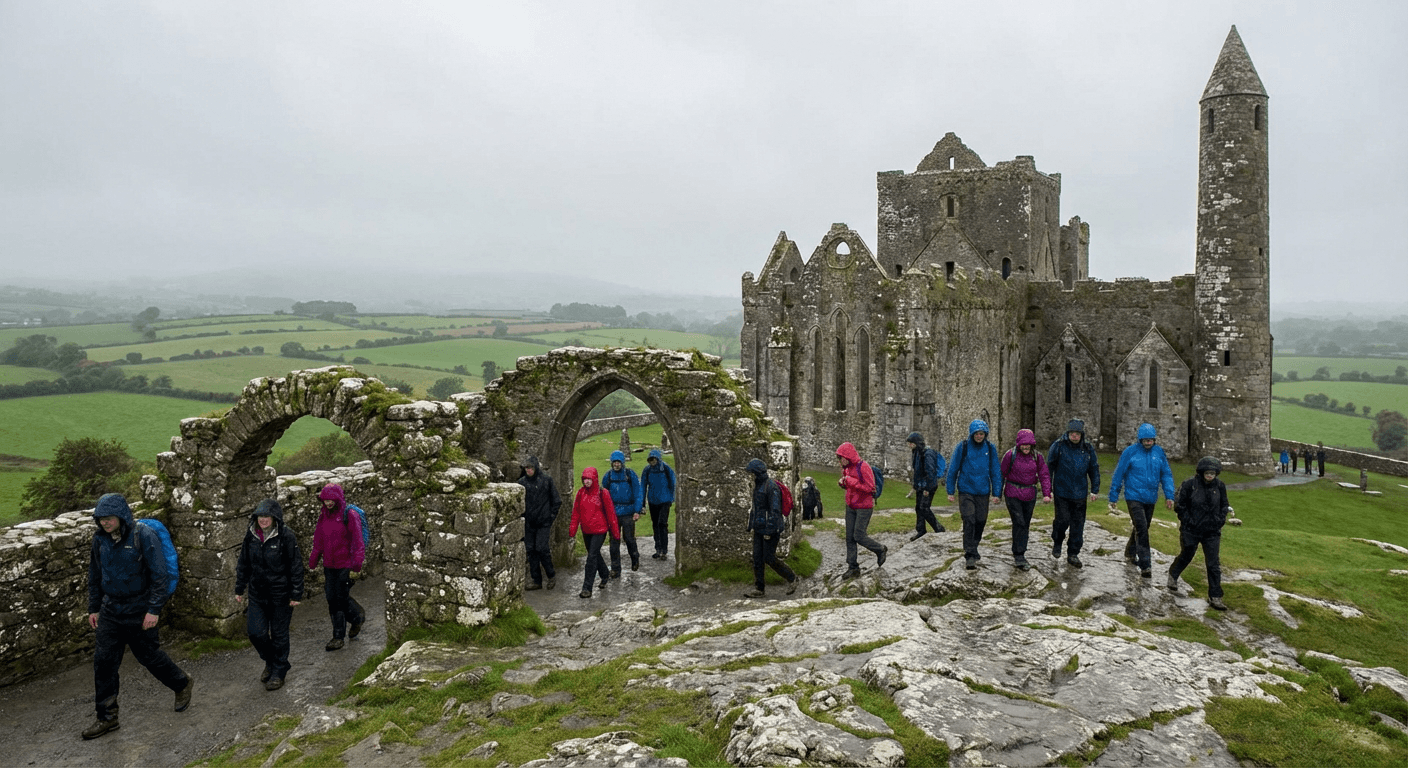

There is a moment at the Rock of Cashel when the wind drops and the voices of tour groups fade, and you are left alone with something ancient. The limestone outcrop rises abruptly from the Golden Vale of County Tipperary, crowned by a cluster of medieval buildings that have witnessed nearly a thousand years of Irish history. This is St. Patrick's Rock, the legendary site where Ireland's patron saint baptised King Aengus in the fifth century — or so the story goes. What remains is a hauntingly beautiful ecclesiastical complex: a twelfth-century round tower, a High Cross covered in weathered biblical scenes, a Gothic cathedral whose roof was removed by Oliver Cromwell's artillery, and a frescoed chapel that somehow survived the centuries intact.

Most visitors arrive at the Rock of Cashel expecting a quick stop on the drive from Dublin to Cork. They leave two hours later, slightly dazed, having wandered through one of Ireland's most atmospheric sacred sites. The place demands slow exploration. Every carved stone has a story — the shepherd who became a bishop, the Viking raiders who met their match, the Cistercian monks who built their abbey in the shadow of the rock and named it simply "the Horreum" — the granary.

This guide covers everything you need to know about visiting the Rock of Cashel and its often-overlooked neighbour, Hore Abbey. We will walk through the site's layered history, explain what you are actually looking at (those guidebooks assume you know your Romanesque from your Gothic), and share practical tips that will make your visit far more rewarding than the average coach tour sprint through the cathedral. This is part of our comprehensive guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub, which also covers Skellig Michael, Glendalough, and Croagh Patrick.

The Legend of St. Patrick's Rock: Myth Meets Limestone

Before the cathedral, before the round tower, before the High Kings of Munster built their fortress here, there was a legend. According to tradition, St. Patrick arrived at the Rock of Cashel in 450 AD and found the local king, Aengus, ruling from this limestone outcrop. The story goes that Patrick converted Aengus to Christianity and baptised him on the rock itself — accidentally driving his crozier through the king's foot in the process. Aengus, believing this was part of the ritual, endured the pain without complaint.

Whether this actually happened is, of course, impossible to verify. What we do know is that by the early medieval period, the Rock of Cashel had become the seat of the Kings of Munster, one of the four ancient provinces of Ireland. The kings built a fortress here not for religious reasons but for military ones. The rock is a natural defensive position, visible for miles across the flat Tipperary countryside. Attackers could be spotted long before they arrived, and the steep sides made the fortress virtually impregnable.

The transition from royal fortress to ecclesiastical centre happened gradually. In 1101, the reigning King of Munster, Muirchertach Ua Briain, handed the Rock of Cashel over to the Church. Whether this was an act of piety or political manoeuvring is still debated by historians — probably it was both. What matters is that the site became one of Ireland's great monastic centres, attracting pilgrims, scholars, and artisans for centuries.

The name "St. Patrick's Rock" stuck, and the legend gave the site its spiritual authority. Even today, visitors touch the stones where Patrick supposedly walked, though the actual buildings date from several centuries after his death. It is a classic Irish conflation of myth and history, where the truth of the story matters less than its power.

Cormac's Chapel: Ireland's Finest Romanesque Building

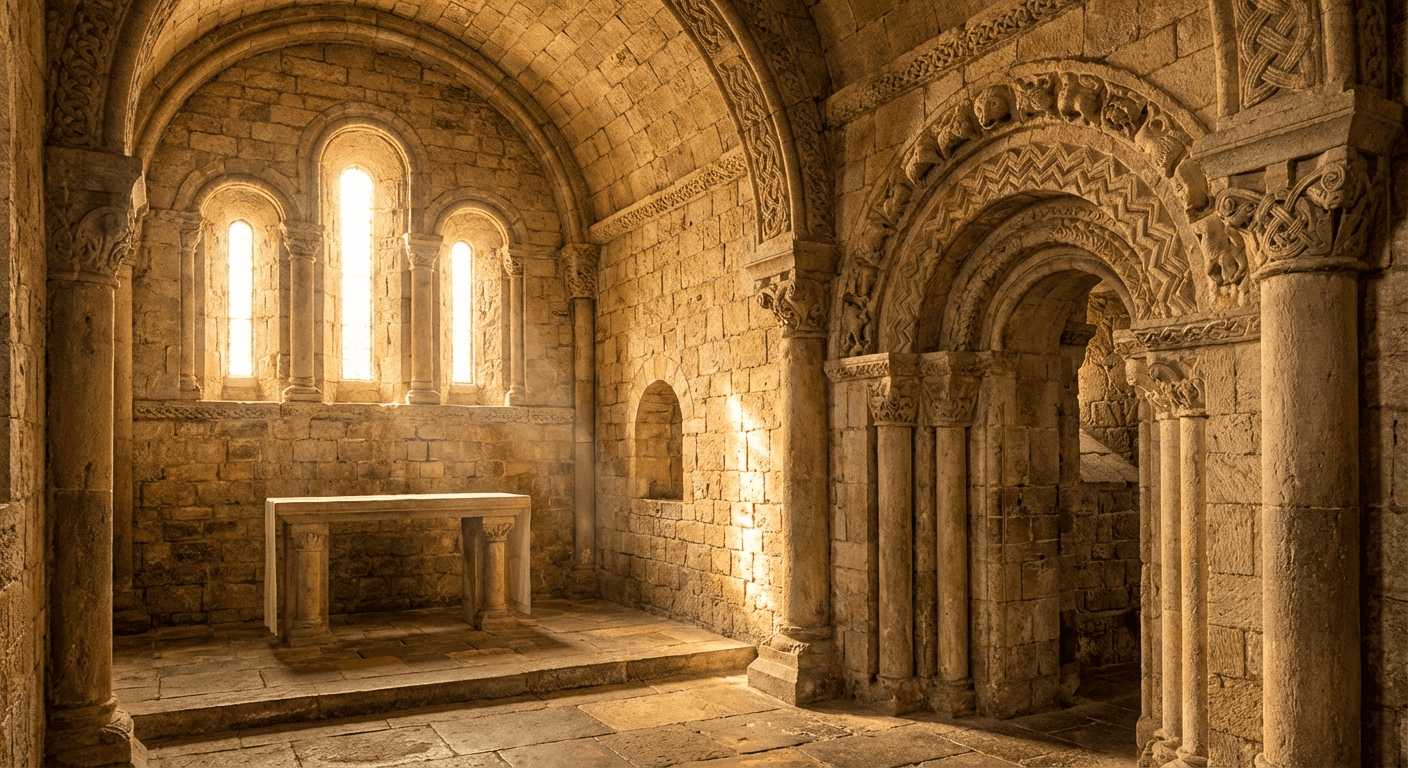

If you visit the Rock of Cashel for only one reason, make it Cormac's Chapel. Built between 1127 and 1134 by Bishop Cormac Mac Carthaig (a member of the same dynasty that had ruled Munster from this rock), this is arguably the finest Romanesque church in Ireland — and one of the best-preserved in Europe.

The chapel is small, cruciform in plan, and absolutely covered in stone carving. The west doorway features an arch of chevron patterns leading to a tympanum depicting an animal fight — probably symbolic rather than purely decorative, though the exact meaning remains mysterious. The nave has a ribbed vault (rare for this period) and blind arcading with carved capitals showing human heads, animals, and interlace patterns that would not look out of place in a Viking art collection.

What makes Cormac's Chapel extraordinary is that it survived at all. Ireland's medieval churches were systematically stripped of their decoration during the Reformation and the Cromwellian wars. Cormac's Chapel escaped relatively unscathed, though the roof was replaced in the nineteenth century and the interior was heavily restored in the 1990s. The restoration work revealed fragments of medieval wall paintings — now protected behind glass but still visible to visitors.

What to Look For:

The two towers flanking the chapel's entrance — one round, one square, representing different phases of construction. The sarcophagus in the north transept, carved from a single block of stone and possibly containing the remains of Cormac himself. The medieval frescoes on the east wall, faded but still discernible, showing scenes from the life of St. Patrick. The unusual combination of Irish and Continental influences in the stone carving — evidence of the cosmopolitan connections of medieval Irish clergy.

Cormac's Chapel has limited capacity and operates on a timed entry system during busy periods. Arrive early or book ahead in summer to guarantee entry.

The Cathedral and Round Tower: Seven Centuries of Worship

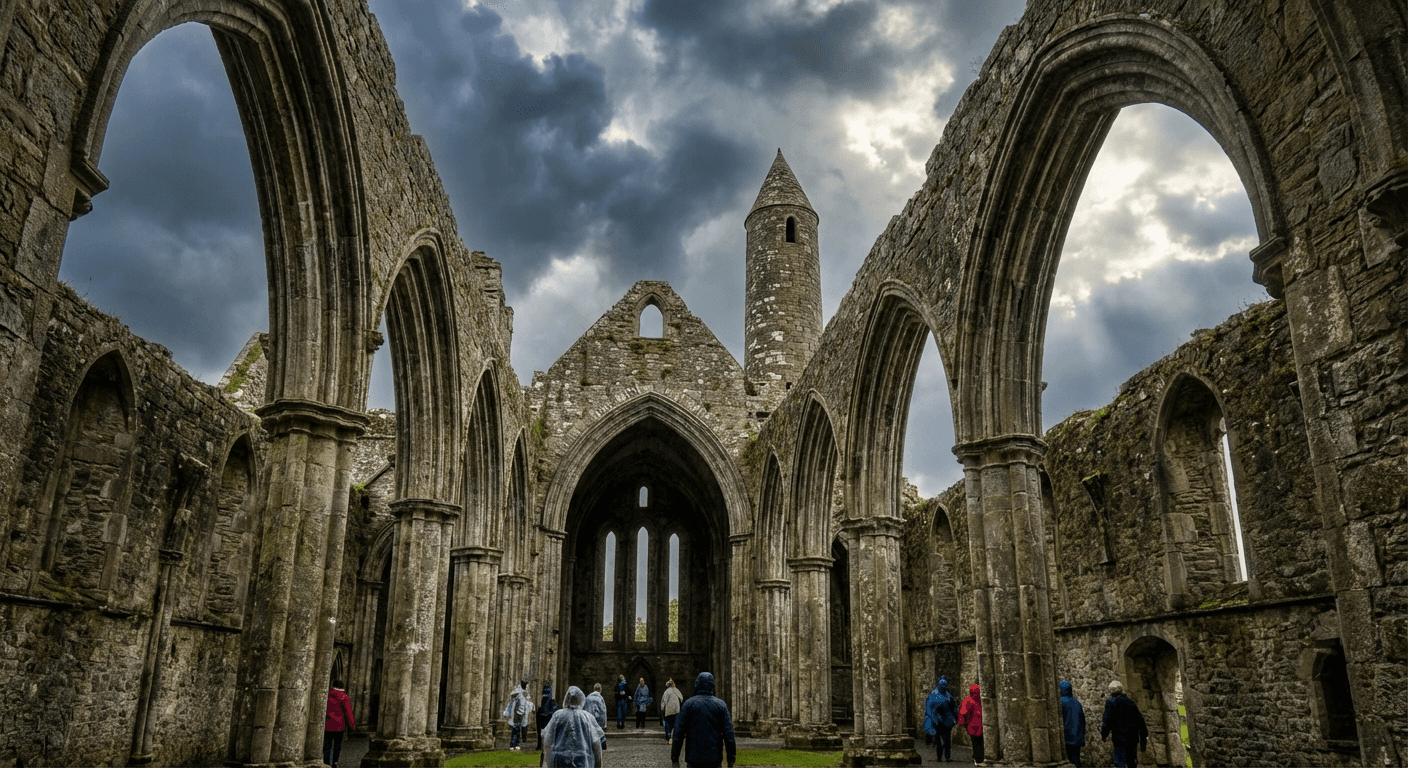

The bulk of what visitors see at the Rock of Cashel is the thirteenth-century cathedral, built in the Gothic style when the earlier chapel proved too small for the growing monastic community. It is a substantial building — 28 metres long with a central tower that would have soared above the surrounding countryside. Today the roof is gone, removed by Cromwellian forces in 1647 after they massacred the defending garrison, and the building stands open to the Irish sky.

This roofless state gives the cathedral a peculiar grandeur. Without the ceiling, the scale of the Gothic arches becomes more apparent. Light floods through the traceried windows (most now without glass), creating shifting patterns on the stone floor. On a rainy day — and this is Ireland, so that is most days — water pools in the flagstones and the whole space feels like a sacred ruin, suspended between use and abandonment.

The round tower stands near the cathedral's northwest corner, the oldest structure on the rock. Built in the early twelfth century, it rises 28 metres with its conical roof still intact — unusual, as most Irish round towers lost their caps centuries ago. These towers served multiple purposes: bell towers, lookout posts, refuges during Viking raids, and symbols of monastic status. The entrance is positioned several metres above ground level, accessible only by ladder that could be drawn up in times of danger.

The Scully's Cross, a nineteenth-century high cross that dominates the cathedral's interior, commemorates a local family but stylistically fits the medieval atmosphere. Nearby stands the original twelfth-century High Cross, its biblical scenes weathered to abstraction — Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Daniel in the lions' den, all carved with the confidence of artists who knew their work would last centuries.

Hore Abbey: The Forgotten Neighbour

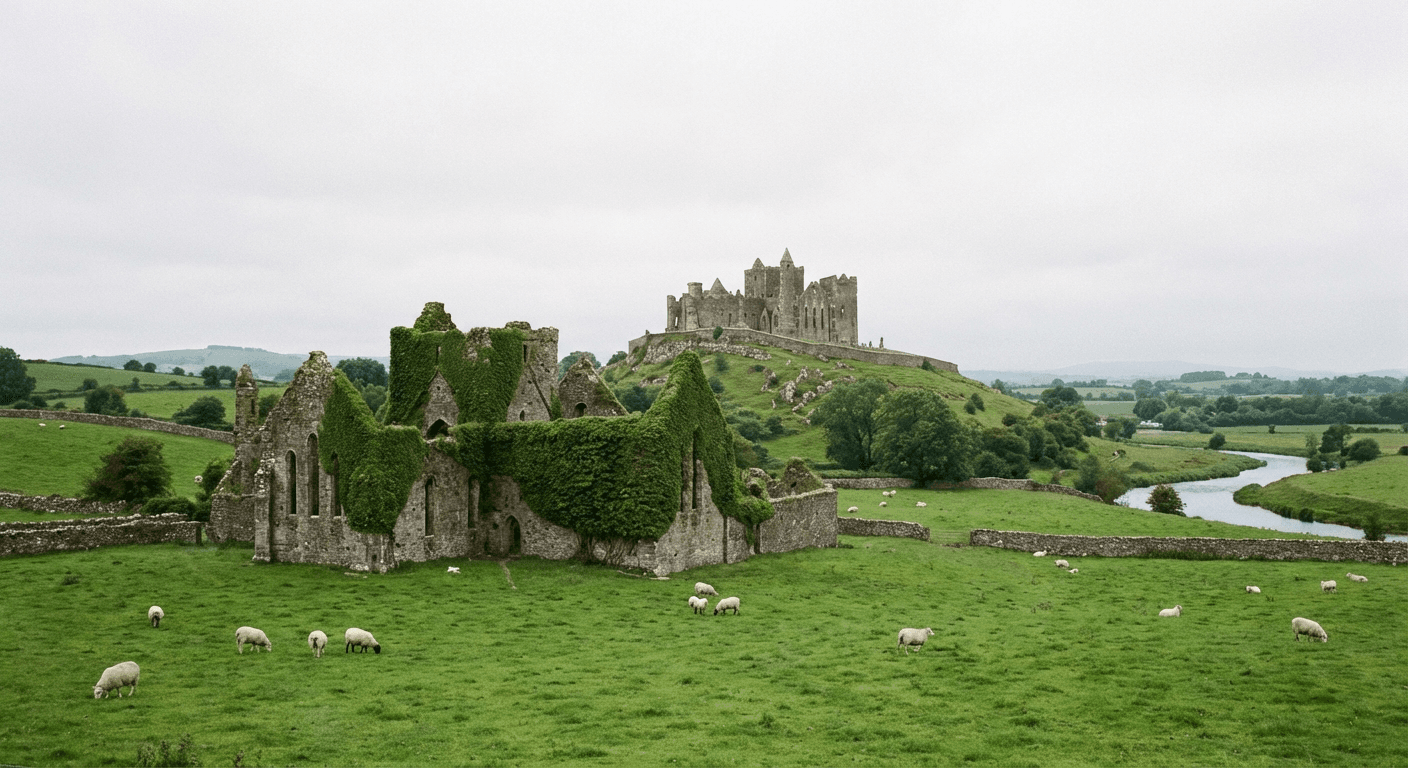

Most visitors to the Rock of Cashel never see Hore Abbey, and that is a shame. Just 500 metres west of the rock, across a field that often contains grazing sheep, stands one of Ireland's most atmospheric Cistercian ruins. Unlike the Rock of Cashel, which is managed by the Office of Public Works with visitor centre, ticket gates, and guided tours, Hore Abbey is simply... there. No admission fee, no opening hours, no crowds. Just the remains of a thirteenth-century monastery sitting in a field, waiting for whoever bothers to walk over.

The abbey was founded in 1270 by the Archbishop of Cashel, who evicted the existing Benedictine monks and invited Cistercians from Mellifont to take their place. The Cistercians were the reformers of medieval monasticism, emphasising simplicity, manual labour, and strict adherence to the Rule of St. Benedict. They built their churches without towers, with plain walls and minimal decoration — a deliberate rejection of the ornate styles seen at the Rock of Cashel.

What remains at Hore Abbey is the church, chapter house, and cloister. The church is cruciform with a tall central tower that collapsed in the nineteenth century (the scar is still visible). The east window is a fine example of Irish Gothic, its tracery still intact despite centuries of exposure. The cloister arcades have mostly fallen, but enough remains to suggest the peaceful enclosed garden where monks once walked while reciting the offices.

Why Visit Hore Abbey:

Solitude. On most days you will have the ruins entirely to yourself. The perspective. Looking back at the Rock of Cashel from here gives you the classic postcard view, but without the postcard crowds. Understanding the contrast. Seeing the simple Cistercian architecture alongside the ornate Rock of Cashel helps explain the religious divisions of medieval Ireland. It is free, always open, and takes twenty minutes to explore properly.

The walk from the Rock of Cashel takes about ten minutes. Exit the visitor centre, turn right onto the road, and look for the abbey ruins in the field to your left. There is a small gate for pedestrian access.

Practical Tips for Visiting the Rock of Cashel

Getting There

The Rock of Cashel sits just outside the town of Cashel in County Tipperary, roughly 90 minutes from Dublin and 45 minutes from Cork. By car, take the M8 motorway and follow signs for Cashel — the rock is visible from miles away, so navigation is straightforward. There is a large car park at the visitor centre (€4 for the day).

Public transport is limited but possible. Bus Éireann runs services from Dublin and Cork that stop in Cashel town, from which it is a 15-minute walk uphill to the rock. The journey takes about two hours from either city.

Tickets and Hours

The Rock of Cashel is managed by the Office of Public Works. Opening hours vary by season: Summer (May-September) 9:00 AM — 6:00 PM. Winter (October-April) 9:00 AM — 4:30 PM. Last admission 45 minutes before closing.

Admission prices (2026): Adults €8, Seniors/Students €6, Children under 12 Free, Families €20.

Best Time to Visit

Early morning or late afternoon offers the best light for photography and fewer crowds. Midday in summer can be busy with coach tours. The rock is exposed and windy — bring a jacket even on apparently warm days.

What to Wear

Sturdy shoes are essential. The rock surface is uneven limestone, worn smooth in places by centuries of foot traffic. In wet weather it becomes slippery. The cathedral has no roof, so you will be exposed to whatever weather Ireland provides.

Facilities and Photography

There is a small visitor centre with toilets, a gift shop, and limited refreshments. The town of Cashel, a 10-minute walk downhill, has several pubs and restaurants. The well-regarded Chez Hans restaurant sits in a former chapel near the rock — reservations recommended.

Photography is permitted throughout the site, including inside Cormac's Chapel (no flash). Tripods require special permission. The best shots are usually from the approach road or from Hore Abbey, capturing the rock rising above the surrounding countryside.

Why a Historical Expert Changes Everything

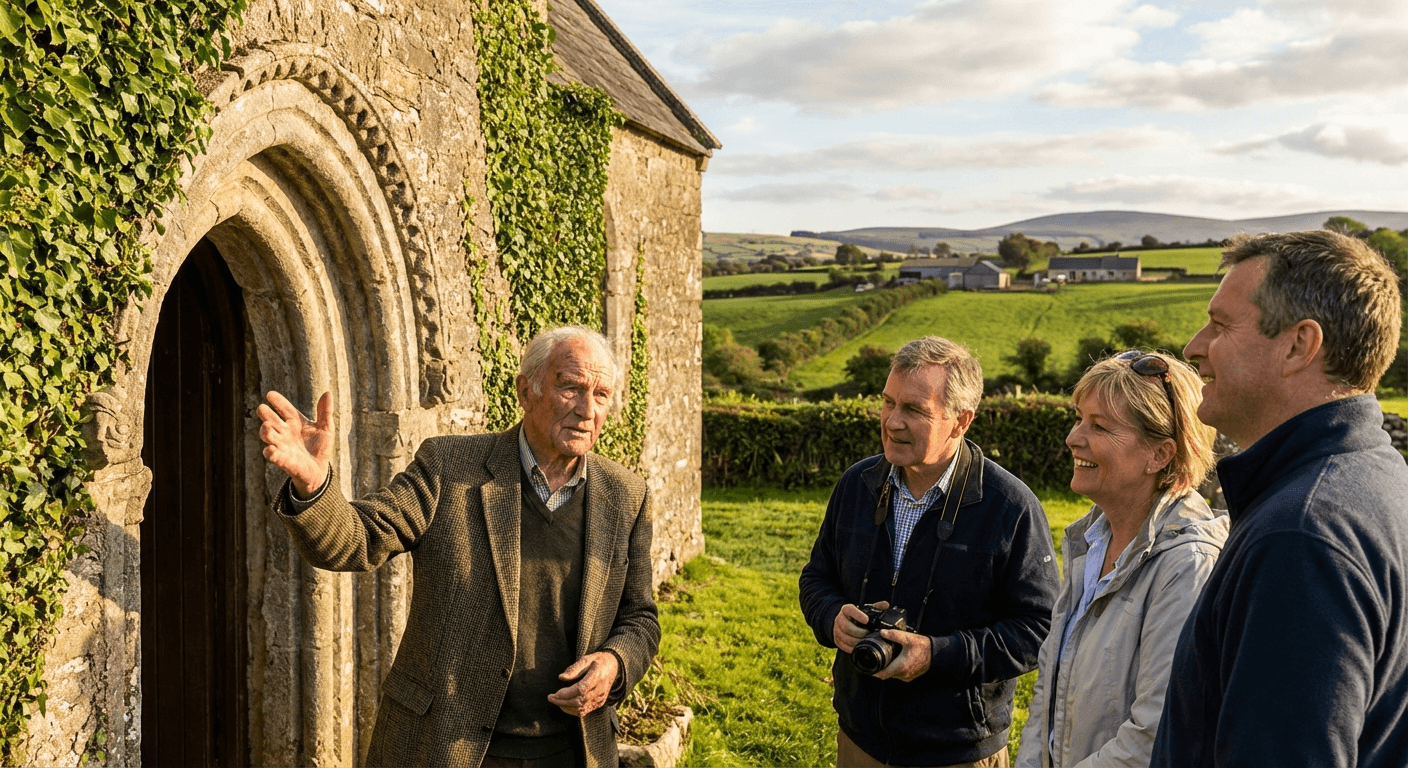

You can visit the Rock of Cashel on your own. Thousands do every year, clutching their guidebooks and audio guides, squinting at weathered carvings and wondering what they are supposed to be seeing. You will enjoy it. The place is magnificent regardless.

But here is what most travel blogs will not tell you: without someone who knows the context, you are looking at old stones. With the right guide, you are looking at a thousand years of Irish history, compressed into limestone and carved by hands that knew they were building for eternity.

A Historical Expert who specialises in medieval Ireland will show you the Viking influence in Cormac's Chapel's interlace patterns. They will explain why the round tower entrance is positioned so high (hint: it was not just for defence). They will point out the stone where Oliver Cromwell's artillery struck, and tell you about the massacre that followed. They will read the faded Latin inscriptions and explain why the Cistercians at Hore Abbey deliberately built their church without decoration.

More than that, they will connect the Rock of Cashel to the broader story of Sacred Ireland. This site does not exist in isolation. It is part of a network of medieval monastic centres — Glendalough, Clonmacnoise, Skellig Michael — that shaped Irish culture and preserved learning through the Dark Ages. A guide who knows this landscape can show you how the Rock of Cashel fits into the larger pattern, and why it matters.

The practical benefits matter too. Your guide handles the tickets, knows the best times to visit Cormac's Chapel (limited capacity, timed entry), and can arrange access to areas closed to general visitors. They know where to park, where to eat, and which of the nearby sites are worth your time.

Browse Historical Experts in County Tipperary on Irish Getaways and book someone who can turn old stones into living history.

Nearby Sites and Extended Itinerary

The Rock of Cashel deserves a full day, but the surrounding area rewards exploration. If you have time, consider these additions:

The Swiss Cottage — A charming ornamental cottage built in the early 1800s by Richard Butler, 12th Baron and 1st Earl of Glengall, as a hunting lodge and romantic retreat. Located about 2 kilometres from Cashel, it features thatched roofs, Gothic windows, and an interior restored to Regency-era splendour. Open for guided tours in summer.

Cahir Castle — One of Ireland's largest and best-preserved medieval castles, located 15 minutes south of Cashel. Built in the thirteenth century, it retains its keep, walls, and towers largely intact. The castle has appeared in several films, including Excalibur and Braveheart.

The Vee Pass — A scenic mountain drive through the Knockmealdown Mountains, about 30 minutes south of Cashel. The road winds through heather-covered hills with views across Tipperary and Waterford. Best in late summer when the rhododendrons bloom.

Holycross Abbey — A restored Cistercian abbey 20 minutes north of Cashel, named for a fragment of the True Cross it once housed. The abbey was carefully restored in the 1970s and offers a contrast to the ruined state of Hore Abbey — here you can see what a medieval monastery looked like when complete.

For those exploring Sacred Ireland more broadly, the Rock of Cashel pairs well with Glendalough (2 hours northeast) and the Holy Wells of Ireland (scattered throughout the region). A Private Driver can efficiently connect these sites, turning a single-day visit into a multi-day pilgrimage through Ireland's spiritual landscape.

Conclusion

The Rock of Cashel rewards those who take their time. This is not a site for rushing through, ticking off the highlights, and moving on to the next attraction on your list. The limestone outcrop has been a place of power for fifteen centuries — fortress, royal seat, monastic centre, pilgrimage destination — and that accumulated history requires slow exploration to appreciate.

Come early in the morning, before the coach tours arrive. Stand in the roofless cathedral and listen to the wind. Examine the carvings on Cormac's Chapel and wonder about the hands that made them. Walk down to Hore Abbey and sit among the ruins, looking back at the rock that dominates the landscape.

This is Sacred Ireland at its most tangible — not myth or legend, but stone and mortar, carved by people who believed they were building for the eternal. For more on Ireland's sacred sites, monastic heritage, and ancient pilgrimage routes, see our complete guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

For a complete overview of Ireland’s most important ancient and spiritual locations, see our master guide to Sacred Ireland.

Related Sacred Sites

Before Cashel became the seat of Munster's Kings, the Hill of Tara was the legendary seat of the High Kings of Ireland.

Its strategic importance contrasts with the scholarly focus of monastic settlements like Clonmacnoise.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.