The Hill of Tara: Walking the Sacred Seat of the High Kings

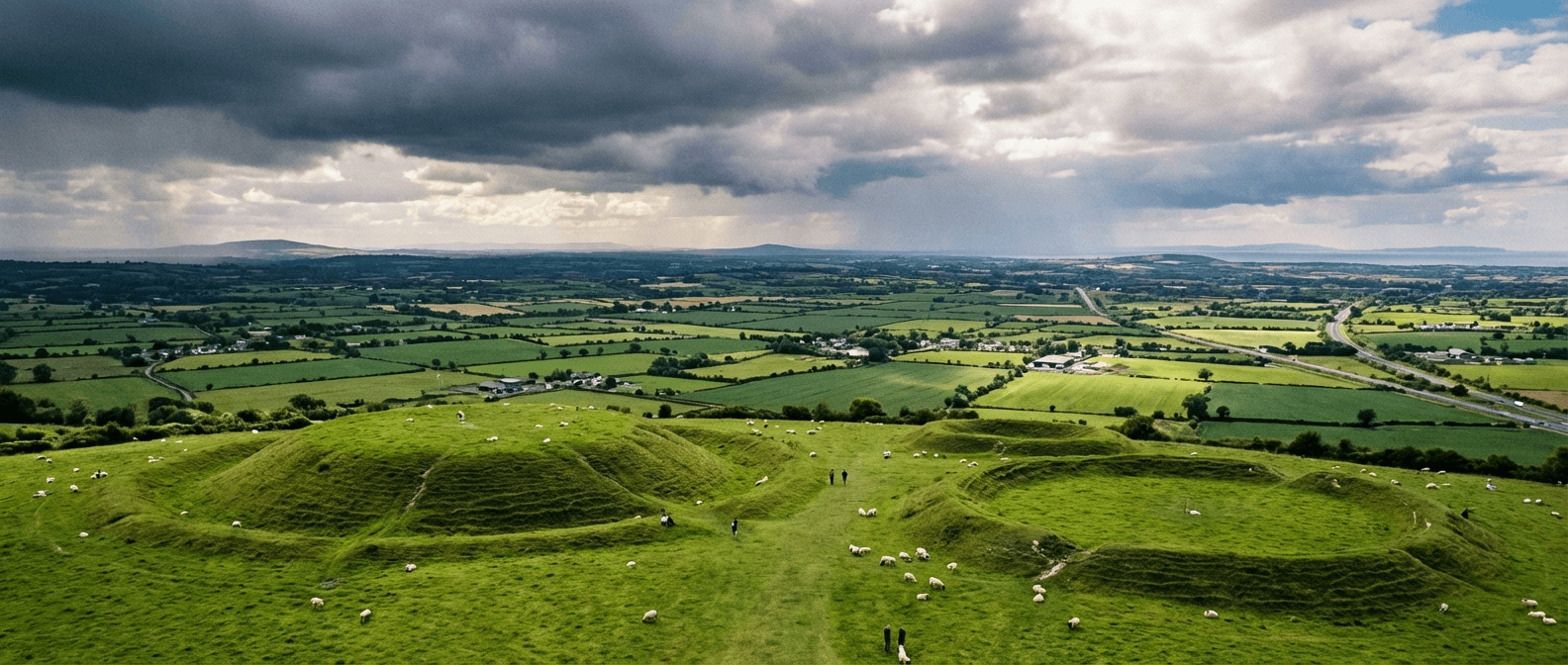

There is a hill in County Meath, barely 150 metres above sea level, from which you can see a quarter of Ireland. On a clear day, the view extends from the Dublin Mountains to the Mourne Mountains, from the Wicklow Hills to the lake-filled midlands. For three thousand years, this modest elevation was the most important place in Ireland — the seat of the High Kings, the spiritual and political heart of a island nation.

The Hill of Tara is not spectacular in the way of Skellig Michael or the Rock of Cashel. There are no soaring cliffs, no intact medieval buildings, no dramatic ruins rising against the sky. What remains is subtle: earthworks, ditches, standing stones, the faintest traces of buildings that have been grassed over for centuries. You must walk the site slowly, read the interpretive panels, use your imagination to see what was once here — a palace complex, a ceremonial centre, a gathering place for the powerful and the holy.

But that subtlety is precisely what makes Tara special. This is not a monument preserved in aspic. It is a landscape that has been continuously sacred for millennia, adapting to each age that claimed it. The Neolithic people who first raised earthworks here. The Bronze Age chieftains who buried their dead in passage tombs. The Iron Age kings who claimed divine right through the Lia Fáil, the Stone of Destiny. The medieval monks who built churches among the pagan remains. The nineteenth-century nationalists who rallied here for Irish independence. And the modern visitors who come seeking connection with a past that still echoes.

This guide covers everything you need to know about visiting the Hill of Tara — what you are looking at, why it mattered, and how to experience it as more than just a green hill with some bumps. This is part of our comprehensive guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

The Sacred Landscape: Understanding What You Are Seeing

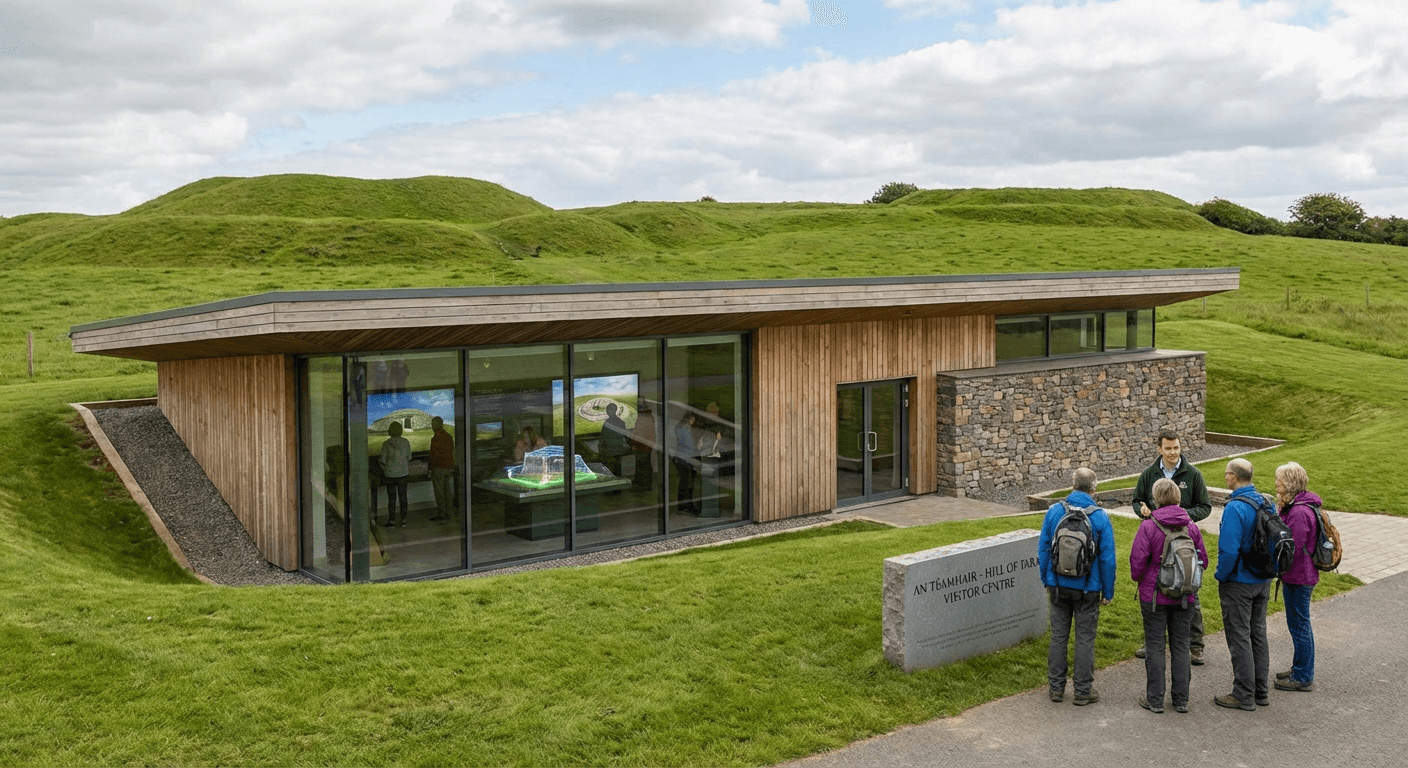

Arriving at Tara for the first time can be disappointing. The car park is modest. The visitor centre is a converted church. The monuments are grassy bumps and ditches that require explanation to appreciate. Without context, Tara looks like any other Irish hill.

The key is understanding the layout. The Hill of Tara is not a single site but a complex of monuments spread across two kilometres of ridge. The main areas are: The Royal Enclosure (Ráith na Ríogh): The heart of Tara, a large circular earthwork about 300 metres in diameter. Inside are two linked earthworks: the Forradh (the King's Seat) and Teach Cormaic (Cormac's House). These are not houses in the modern sense but ceremonial enclosures where the High Kings were inaugurated and conducted affairs of state.

The Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny): Standing within the Forradh, this weathered pillar stone is said to have roared when touched by the rightful High King. The stone you see today may not be the original — it was moved in the nineteenth century — but the association remains powerful. Touch it yourself and see if you hear anything.

The Mound of the Hostages (Dumha na nGiall): The oldest monument on Tara, a Neolithic passage tomb dating to around 3000 BC. It predates the kingship by millennia but was incorporated into the sacred geography of the site. Its name comes from the medieval period, when it was supposedly used to hold hostages from subjugated kingdoms.

The Banqueting Hall (Teach Miodhchuarta): A long, narrow earthwork that stretches for 200 metres. Despite the name, it was probably not a hall for eating but a ceremonial avenue or processional way. Its exact function remains debated.

The Rath of the Synods (Ráith na Seanadh): A complex earthwork just north of the Royal Enclosure, named for the synods said to have been held here in the early Christian period. Excavations revealed evidence of both pagan and Christian activity.

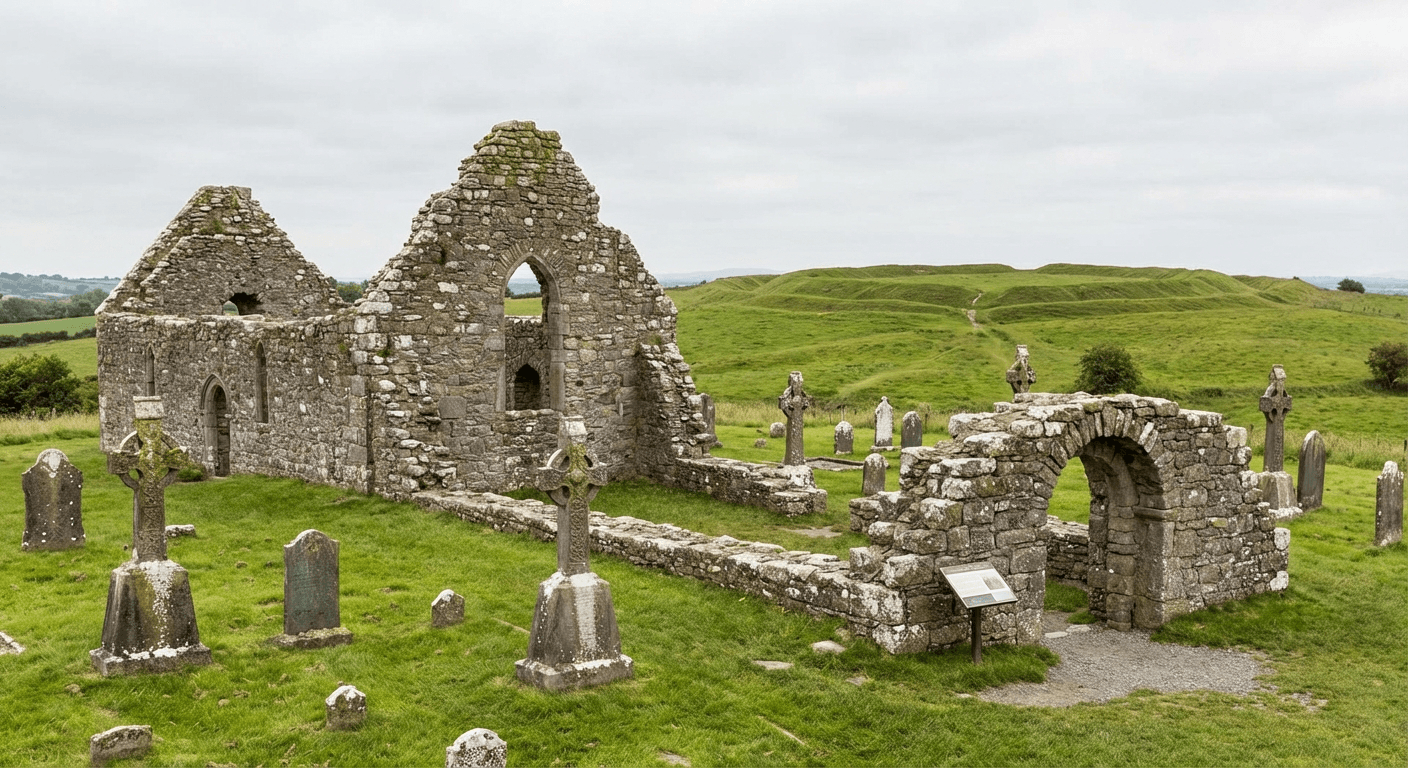

The Church and Graveyard: Two churches and a surrounding graveyard occupy the southern part of the site. The larger church is medieval; the smaller is a modern reconstruction. Saint Patrick is said to have preached here, lighting the Paschal fire that challenged the pagan kings. Walking between these sites takes about an hour. The ground is uneven and can be muddy after rain. Sturdy shoes are essential.

The High Kings: Politics and Myth at Tara

The Hill of Tara was the seat of the High Kings of Ireland for centuries — or at least, that is what the medieval texts tell us. The reality was probably more complex. Ireland never had a unified kingdom in the modern sense. The High King was more of a first among equals, acknowledged by the provincial kings but rarely exercising direct control over the whole island.

Still, Tara mattered. To be inaugurated at Tara was to claim legitimacy derived from the land itself. The ceremony involved the Lia Fáil, the stone that supposedly roared to confirm the rightful king. It involved rituals that connected the king to the fertility of the land — the famous marriage of the king to the sovereignty goddess, a mythic trope that persisted in Irish literature long after the pagan religion had vanished.

The most famous High King associated with Tara is Cormac mac Airt, a semi-legendary figure who supposedly ruled in the third century. The stories about Cormac — his wisdom, his justice, his magical abilities — became the template for ideal Irish kingship. Teach Cormaic, the earthwork within the Royal Enclosure, is named for him, though it probably dates to a later period.

Tara's importance declined after the Norman invasion of the twelfth century. The new Anglo-Norman rulers had no interest in maintaining a pagan-inspired kingship site. The last High King to be inaugurated at Tara was probably Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair in 1166. After that, Tara became a symbol rather than a functioning political centre — a reminder of a native Irish sovereignty that had been lost.

Saint Patrick and the Paschal Fire: Christianity Claims Tara

The traditional date for Saint Patrick's arrival at Tara is Easter 433 AD. According to the legend, Patrick and his followers climbed the Hill of Slane, visible from Tara, and lit the Paschal fire — a flame that was supposed to be lit only at Tara, by the High King, to mark the beginning of the pagan festival of Beltane.

The High King, Laoire, saw the fire and demanded that the offenders be brought before him. Patrick arrived, explained the Christian faith, and began converting the court. Some versions of the story say he used the shamrock to explain the Trinity. Others say he performed miracles. All agree that the fire on Slane marked the beginning of the end for pagan Tara.

The historical accuracy of this story is, of course, uncertain. Patrick may never have visited Tara at all. But the legend served an important purpose: it legitimised Christianity by showing it triumphing over paganism at the most sacred site in Ireland. The church that now stands on Tara — rebuilt in the nineteenth century on medieval foundations — commemorates this supposed encounter.

What is certain is that early Christians did build on Tara. The Rath of the Synods contains evidence of early Christian activity, possibly including a church. The nearby church at Skryne, founded by a follower of Patrick, was closely associated with Tara. Christianity did not reject the sacred landscape; it reinterpreted it, claiming the pagan past for the new faith.

This pattern — pagan site, Christian reuse, modern national significance — makes Tara a perfect case study in how sacred landscapes evolve. The same ground has been holy for three thousand years, even as the meaning of that holiness has changed completely.

Walking Tara: A Route for Visitors

The best way to experience Tara is to walk it slowly, following a logical route that builds understanding as you go. Here is a suggested itinerary:

Start at the Visitor Centre: The converted church contains exhibitions explaining the history and archaeology of Tara. The 20-minute audio-visual show is worth watching — it orients you to what you are about to see. Pick up the free site map.

Walk to the Mound of the Hostages: This is the oldest monument on the site, and starting here gives you the chronological foundation. The passage tomb is closed to the public (the entrance is blocked), but you can appreciate its scale and position. Notice how it is aligned with the sunrise on the cross-quarter days — the old Celtic festivals of Samhain and Imbolc.

Continue to the Royal Enclosure: Walk the perimeter of the large circular earthwork, then enter through one of the original entrances. Inside, visit the Forradh and the Lia Fáil. Stand on the raised platform and imagine the inauguration ceremonies that once took place here. The view encompasses half of Ireland — on a clear day, you can understand why this spot was considered the centre of the world.

Walk the Banqueting Hall: Follow the long earthwork south from the Royal Enclosure. Try to picture it as a processional way, with ranks of warriors and druids forming an avenue for the king. Visit the Church and Graveyard: End your walk at the medieval church, which represents the final layer of Tara's sacred history. The graveyard contains memorials to nineteenth-century patriots who saw Tara as a symbol of Irish nationhood.

Allow two to three hours for a proper visit. Tara rewards slow exploration and repeated visits in different weather and light conditions.

The Controversy: Tara and the M3 Motorway

No discussion of Tara in the twenty-first century can ignore the controversy over the M3 motorway, which opened in 2010. The route passes within two kilometres of the hill, cutting through the wider Tara landscape that archaeologists believe was integral to the sacred site.

The campaign to reroute the motorway attracted international attention. Protesters, including the actor Stuart Townsend and poet Seamus Heaney, argued that the motorway would destroy a landscape that had been sacred for three thousand years. The government and road builders countered that the road was essential for development and that no archaeological remains would be directly destroyed.

The road was built. The protests failed. But the controversy raised important questions about how Ireland values its heritage. Was Tara just the hill itself, or was it the entire landscape visible from the hill? Did economic development trump cultural preservation? Who decides what is worth saving?

Visitors to Tara today will see the motorway in the distance, carrying traffic between Dublin and the north. It is a reminder that sacred sites do not exist in isolation from the modern world. They are contested spaces, where different values — economic, cultural, spiritual — collide.

Practical Information for Visiting Tara

Getting There

The Hill of Tara is in County Meath, about 40 kilometres northwest of Dublin. By car, take the M3 motorway to the turnoff for Navan, then follow signs for Tara. The journey takes about 45 minutes from Dublin city centre. There is a large car park at the visitor centre.

Public transport is limited but possible. Bus Éireann operates services from Dublin to Navan, from which you can take a taxi to Tara (about 10 minutes). Some tour companies include Tara in day trips from Dublin that also visit Newgrange and the Boyne Valley.

Visitor Centre and Hours

The visitor centre is open year-round, though hours vary by season: May-September 10:00 AM — 6:00 PM. October-April 10:00 AM — 5:00 PM. Admission is free, though donations are welcome. The centre contains exhibitions, an audio-visual show, toilets, and a small gift shop.

Guided Tours and What to Wear

Free guided tours operate from the visitor centre at regular intervals during the summer. These are highly recommended — Tara is difficult to appreciate without explanation. The guides are knowledgeable and passionate about the site.

The site is entirely outdoors and exposed. The Meath weather can change rapidly. Bring waterproof clothing and sturdy walking shoes. The ground is uneven and can be muddy. Tara combines naturally with a visit to Newgrange and the Boyne Valley, about 20 minutes away. The two sites — Tara as the seat of the High Kings, Newgrange as the tomb of the ancestors — complement each other perfectly. Many visitors do both in a single day.

Why a Historical Expert Makes Tara Come Alive

You can visit Tara on your own. The visitor centre provides basic information, and the site is well signposted. But without expert guidance, you will miss the nuances that make Tara truly extraordinary.

A Historical Expert who specialises in Irish prehistory and early medieval history can transform your visit. They can explain the archaeology — how the earthworks were constructed, what excavations have revealed, how our understanding of Tara has changed over time. They can tell the stories — Cormac mac Airt, Saint Patrick, the nineteenth-century patriots. They can connect Tara to the broader picture of Sacred Ireland, showing how this site relates to Newgrange, Clonmacnoise, and the other great centres of Irish spirituality.

More than that, they can help you see what is no longer visible. Tara is a landscape of memory as much as of stone. The expert guide can help you imagine the feasting halls, the druidic ceremonies, the medieval synods, the nationalist rallies. They can explain why this modest hill mattered so much for so long.

Browse Historical Experts in County Meath on Irish Getaways and book someone who can unlock the secrets of the Seat of the High Kings.

Tara in Modern Ireland: Symbol and Contested Space

The Hill of Tara remains politically potent in modern Ireland. In the nineteenth century, it became a rallying point for Irish nationalism — Daniel O'Connell held a mass meeting here in 1843, calling for repeal of the Act of Union. The 1798 rebellion was commemorated at Tara. The Irish Republican Brotherhood used it as a meeting place.

This nationalist association makes Tara a contested space. For some, it represents authentic Irish identity, pre-colonial and pure. For others, it represents a romanticised, exclusionary vision of Irishness that ignores the complexity of the island's history. The archaeologists who study Tara often find themselves caught between these competing narratives.

What is undeniable is Tara's continued power to move people. Visitors from across the world come here seeking connection — to Irish ancestry, to Celtic spirituality, to something older and deeper than their ordinary lives. Some find it. Others do not. But the seeking matters.

Tara teaches us that sacred landscapes are not static. They change meaning over time, adapting to each age that claims them. The Neolithic farmers who built the Mound of the Hostages would not recognise the Tara of today. But they would recognise the impulse that brings people here — the human need for places that transcend the everyday, that connect us to something larger than ourselves.

Conclusion

The Hill of Tara is not spectacular. It will not take your breath away like Skellig Michael or impress you with architectural grandeur like the Rock of Cashel. What it offers is something rarer: the accumulated weight of three thousand years of continuous human significance.

Walk the earthworks slowly. Touch the Lia Fáil. Stand on the Forradh and look out across the Irish midlands. Imagine the kings who stood here, the druids who counselled them, the saints who challenged them, the patriots who invoked their memory. This is where Ireland, in some sense, began.

For more on Ireland's sacred sites, from Newgrange to Clonmacnoise, from Croagh Patrick to the Holy Wells, see our complete guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

For a complete overview of Ireland’s most important ancient and spiritual locations, see our master guide to Sacred Ireland.

Related Sacred Sites

Tara's significance is deeply connected to the other major Boyne Valley sites, most notably Newgrange and Knowth.

This was the seat of the High Kings, the political equivalent to the great royal centre at the Rock of Cashel.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.