Clonmacnoise: Visiting the "Crossroads of Ireland" on the River Shannon

There is a silence at Clonmacnoise that you do not find at Ireland's better-known monastic sites. No coach parks disgorging fifty tourists at a time. No audio guides chattering in six languages. Just the whisper of wind across the Shannon floodplain, the cry of crows from the round towers, and the standing stones that have watched over this ground for fourteen centuries. This was the "Crossroads of Ireland" — the geographical and spiritual heart of a medieval empire that stretched from Scotland to Italy.

Founded in 544 AD by Saint Ciarán, a young monk who chose this spot where the Slighe Mhór — the Great Highway — forded the River Shannon, Clonmacnoise grew into one of Europe's great monastic cities. At its peak in the tenth and eleventh centuries, it housed thousands of monks, students, and craftsmen. Its scriptorium produced the Annals of Tigernach and the Book of the Dun Cow. Its high crosses were carved by masters whose work would influence Irish art for centuries. Its cathedral hosted the funerals of kings.

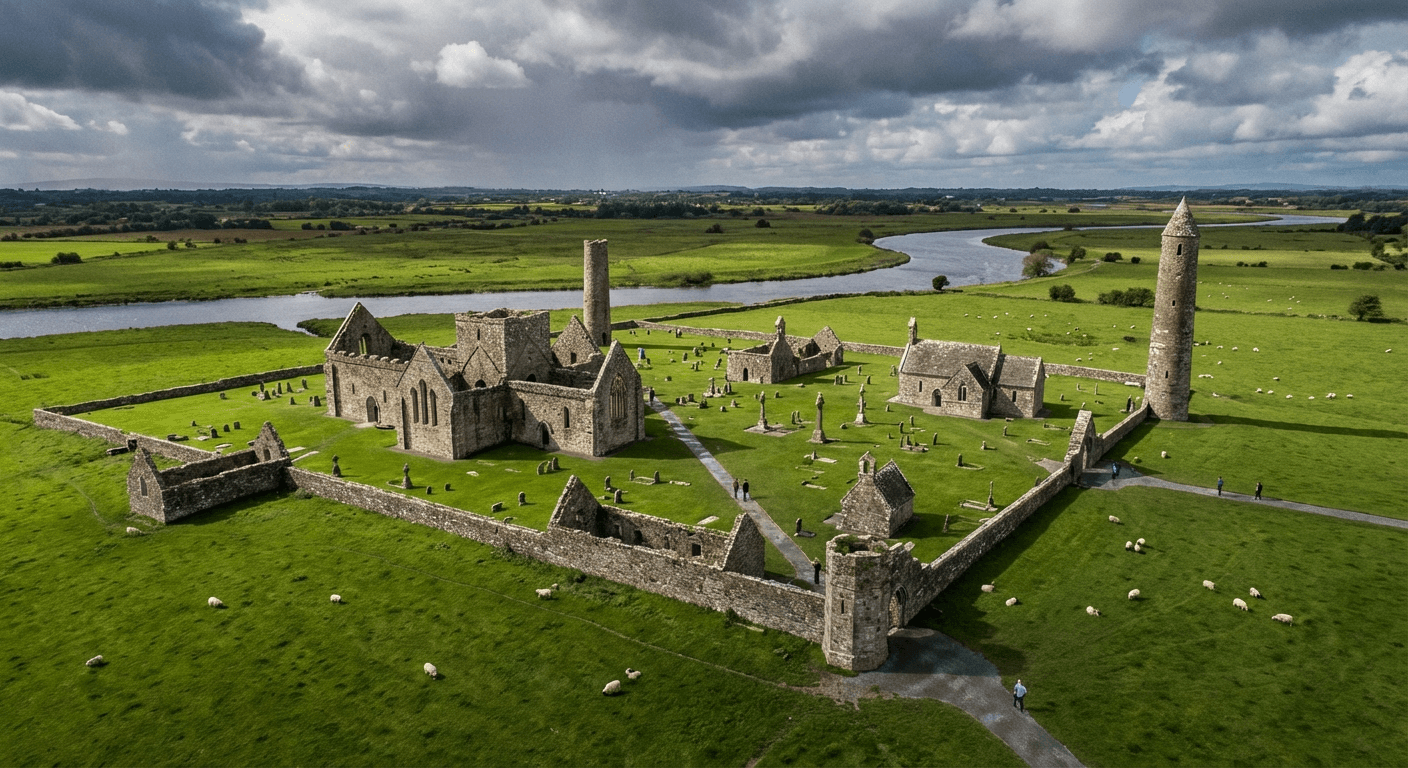

Today, Clonmacnoise is a fragment of its former self — a collection of ruins spread across a flat green field, surrounded by water meadows that flood each winter. What remains is enough to suggest the scale of what was lost: two round towers, a cathedral, nine churches, two high crosses, and thousands of grave slabs carved with the names of forgotten pilgrims. The site demands imagination. You must look at the foundations and see the halls, the workshops, the harbour where boats from France and Germany once unloaded wine and books.

This guide covers everything you need to know about visiting Clonmacnoise — how to get there, what you are looking at, and why this quiet corner of County Offaly deserves a place on any serious exploration of Sacred Ireland. This is part of our comprehensive guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub, which also covers Skellig Michael, Glendalough, and the Rock of Cashel.

Saint Ciarán and the Founding: A Monastery at the Crossroads

Saint Ciarán was young when he founded Clonmacnoise — barely thirty, according to the annals. He had studied at Glendalough under Saint Kevin and at other monastic centres across Ireland. When he sought a place to establish his own foundation, a divine sign supposedly guided him: an old man who revealed that a suitable site would be marked by a "rising of the ground" and the presence of great trees. Ciarán found such a spot where the Esker Riada — a glacial ridge that served as Ireland's main east-west highway — met the River Shannon.

The location was strategic genius. The Shannon was Ireland's great north-south artery. The Esker Riada connected the east coast (Dublin, the Irish Sea, continental Europe) with the west (Galway, the Atlantic). Whoever controlled this junction controlled trade, information, and influence. Ciarán positioned his monastery at the centre of everything.

He did not live to see its greatness. Ciarán died of plague in 549 AD, only months after founding the monastery. But his successors built on his vision. By the eighth century, Clonmacnoise had become a monastic city — not just a place of worship but a centre of learning, craft, and commerce. Its scriptorium produced manuscripts whose beauty still astonishes. Its metalworkers created the shrines and reliquaries that made Clonmacnoise a pilgrimage destination. Its scholars compiled the annals that remain our primary source for early Irish history.

The "Crossroads of Ireland" nickname stuck. Kings and bishops fought for control of the monastery throughout the medieval period. The Annals of Clonmacnoise record fires, Viking raids, and political intrigue that would not be out of place in a modern thriller. Through it all, the monastery endured — until the seventeenth century, when it was finally abandoned and left to decay.

The Cathedral and Temple Ciarán: Where Saint Ciarán Lies

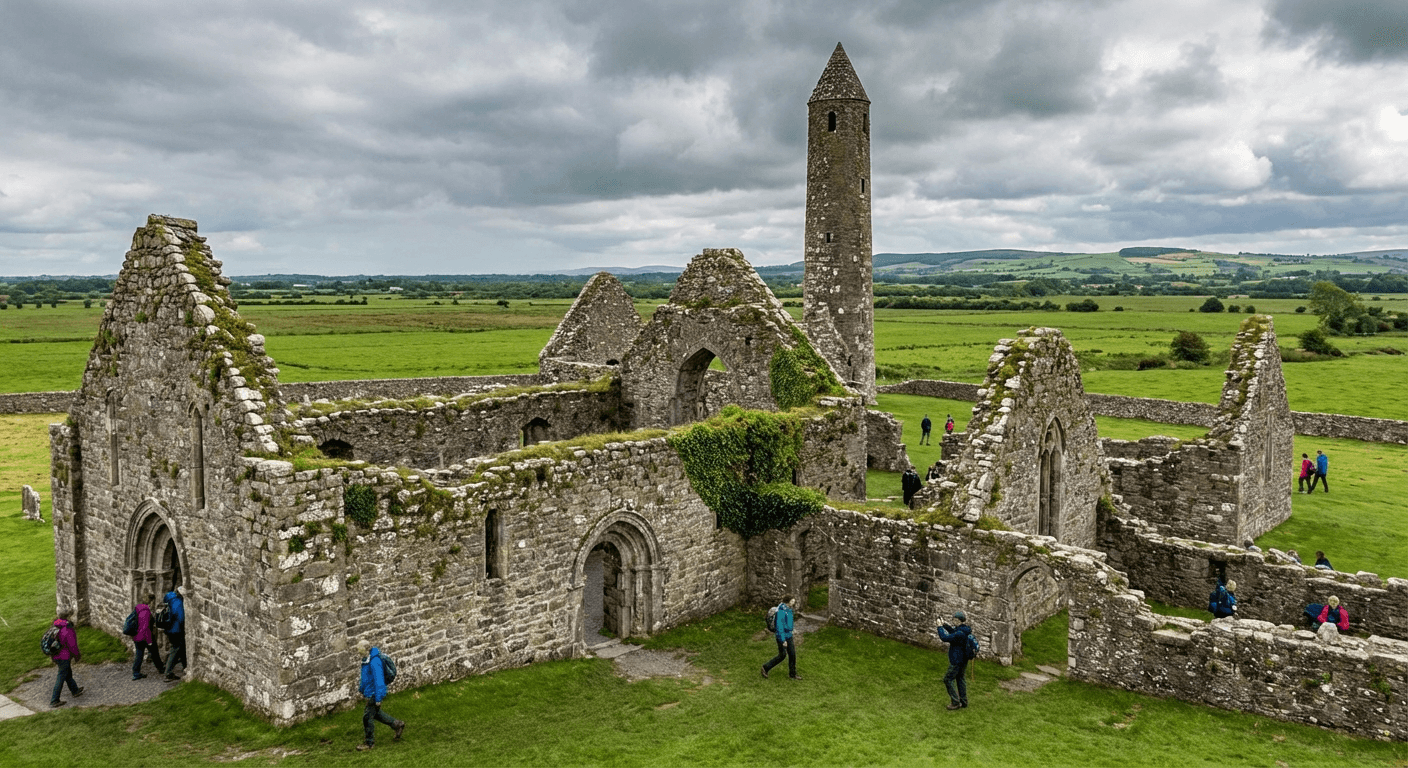

The cathedral dominates the centre of the site — or rather, its ruins do. Built in the tenth century and extended over the following centuries, it was the largest church at Clonmacnoise and the burial place of its founder. The building follows the standard Irish monastic plan: a long nave with side aisles, a chancel at the east end, and a west doorway that once faced the approach road.

What you see today is a roofless shell, the walls standing to various heights. The west doorway still retains its Romanesque arch, carved with chevron patterns and animal heads in the style of the period. Inside, the floor is paved with grave slabs — some medieval, some from the nineteenth century when the site became a place of burial once again. Look for the stone marking the grave of Saint Ciarán himself, though his actual remains were likely removed centuries ago.

Adjacent to the cathedral stands Temple Ciarán, a small rectangular church traditionally believed to mark the exact spot where Ciarán built his first cell. The current building dates from the ninth or tenth century, but it occupies a site of continuous significance. Pilgrims once circled the church seven times in prayer — a ritual known as a "pattern" that survived into the twentieth century in some parts of Ireland.

What to Look For

The carved stones set into the cathedral walls, some recycled from earlier buildings. The "Whispering Arch" near the chancel, where two people can hear each other across the width of the church. The grave slabs with their distinctive crosses and inscriptions — many still readable after a thousand years. The contrast between the cathedral's scale and the intimate simplicity of Temple Ciarán.

The Two Round Towers: Fortress and Belfry

Clonmacnoise has two round towers, and they tell different stories about the monastery's evolution. The taller tower, near the cathedral, stands 19 metres high with its conical cap still intact. Built in the twelfth century, it served as both bell tower and refuge — the entrance is positioned several metres above ground level, accessible only by ladder that could be drawn up in times of danger.

The second tower is shorter and stumpier, missing its cap. It stands near Temple Finghin (a ruined church named after a medieval abbot) and dates from a similar period. Some scholars believe it was never completed, or that its upper section collapsed. Others suggest it was deliberately reduced in height at some point.

These towers are typical of Irish monastic architecture — found nowhere else in Europe in this specific form. They served multiple functions: bell towers to call the monks to prayer, watchtowers to spot approaching Vikings, storehouses for valuable relics and manuscripts, and symbols of monastic prestige. The taller the tower, the greater the monastery's status.

Climbing the tower: The taller round tower is occasionally open for guided climbs — check with the visitor centre. The view from the top encompasses the entire site, the winding Shannon, and the flat expanse of the midlands stretching to every horizon. It is worth the effort if you have the opportunity.

The High Crosses: Scripture in Stone

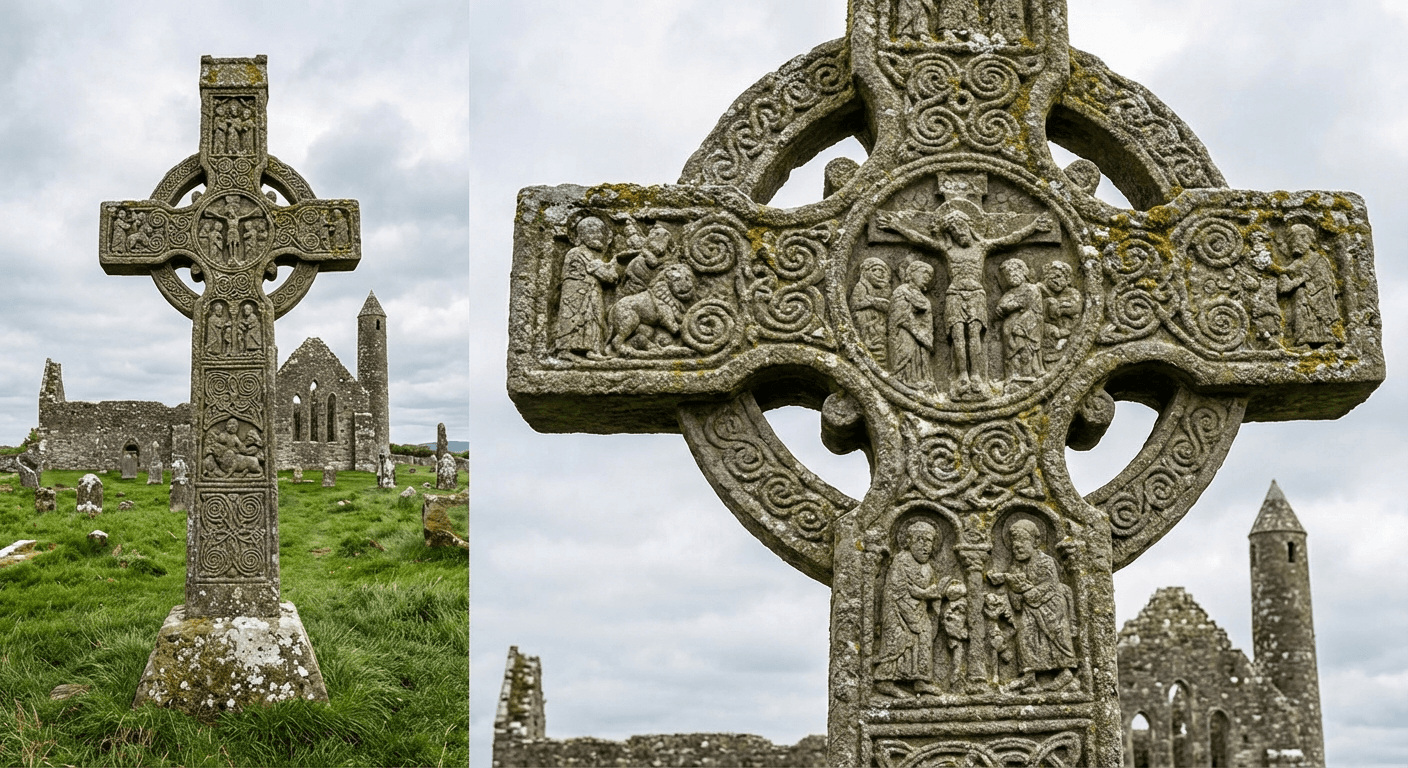

Clonmacnoise's high crosses are among the finest in Ireland — and that is saying something. These were not mere grave markers. They were "scripture in stone," designed to teach biblical stories to a largely illiterate population. Each cross is carved with panels depicting scenes from the Old and New Testaments, arranged so that a pilgrim walking around the cross would encounter the full narrative of salvation history.

The Cross of the Scriptures (also called King Flann's Cross) is the masterpiece. Standing four metres high, it was erected in the early tenth century and depicts the crucifixion, the Last Judgment, Christ in Majesty, and scenes from the life of David. The carving is extraordinarily detailed — you can make out the expressions on faces, the folds of garments, the architectural details of buildings. A modern replica stands on the site today; the original is housed in the visitor centre to protect it from weathering.

The North Cross and South Cross are smaller but equally significant. The North Cross shows the earliest example of the "high cross" form in Ireland — a simple ringed cross with minimal decoration. The South Cross carries scenes from the Old Testament, including Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and David playing his harp.

Reading the crosses: Start at the east face (facing the sunrise) and move clockwise. The scenes are arranged chronologically: creation and fall on the lower panels, the life of Christ in the middle, the Last Judgment at the top. The message is theological but also political — these crosses proclaimed Clonmacnoise's authority and orthodoxy to every pilgrim who approached.

Temples and Churches: A City of Worship

Beyond the cathedral, Clonmacnoise contains eight other churches — each with its own history and architectural character. Most are roofless ruins now, but their foundations reveal a complex sacred landscape that evolved over centuries.

Temple Finghin (the "Church of Finghin") is the most impressive after the cathedral. Built in the twelfth century, it features a fine Romanesque doorway with carved capitals and a small chancel arch. The adjacent round tower (the shorter one) was likely built as a belfry for this church.

Temple Connor (also called Temple Ciarán the second — yes, it is confusing) contains some of the site's oldest visible masonry, with walls that may date to the ninth century. The doorway is particularly interesting, showing the transition from early Irish to Romanesque styles.

Temple Dowling and Temple Hurpan are smaller, later structures — sixteenth-century additions that show the monastery was still active right up to its dissolution. These churches are rougher in construction, reflecting the decline in resources and expertise as the medieval period drew to a close.

The Lady Chapel at the eastern edge of the site was added in the thirteenth century and shows Gothic influences: pointed arches, traceried windows, and a more vertical emphasis than the earlier Romanesque buildings.

Walking among these churches, you can trace the evolution of Irish ecclesiastical architecture from simple stone oratories to sophisticated Romanesque and Gothic structures. Each generation rebuilt and expanded, layering new styles atop older foundations.

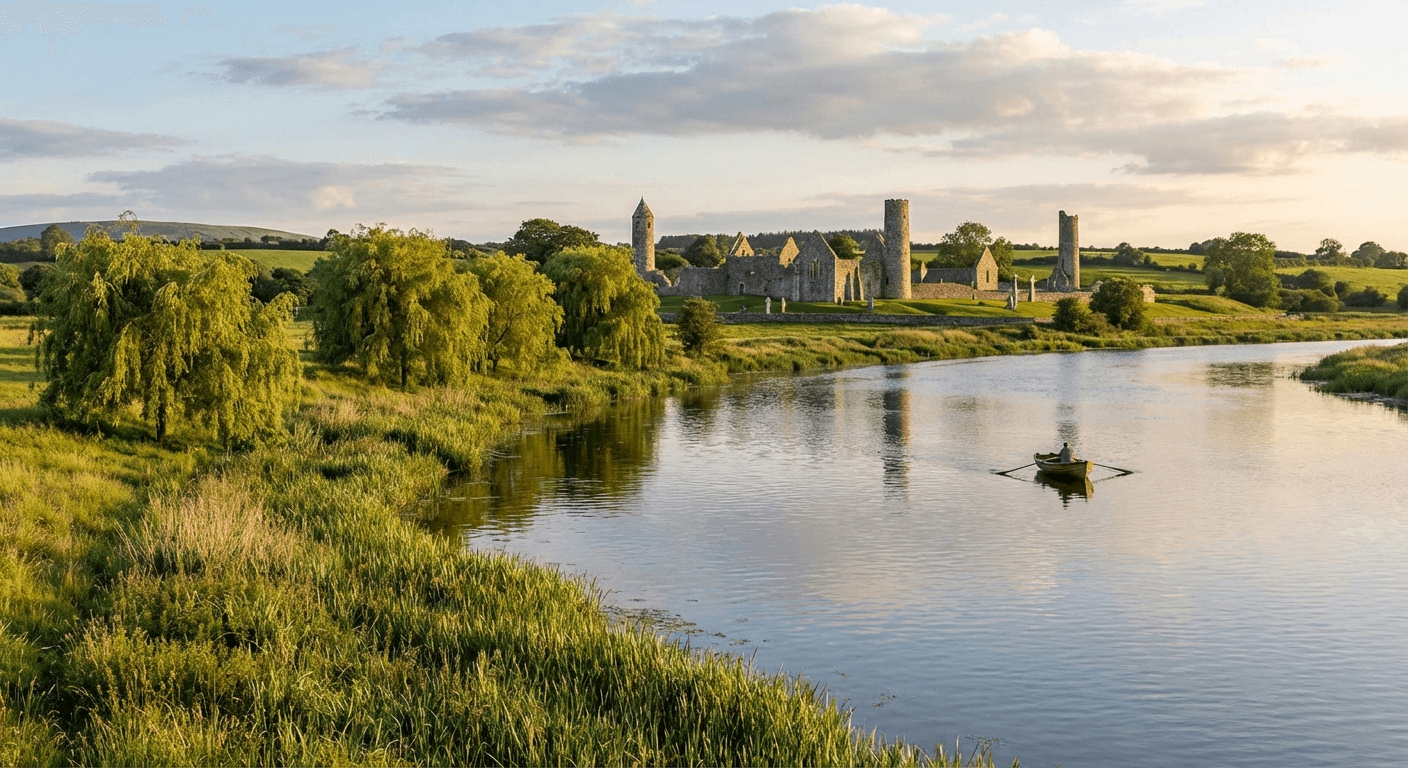

The Shannon Connection: Arrival by Boat

The River Shannon was Clonmacnoise's lifeline. In the medieval period, most visitors arrived by boat — pilgrims from across Ireland, scholars from continental Europe, traders carrying wine and luxury goods. The monastery maintained a harbour on the riverbank, and the abbot controlled tolls and customs duties that made Clonmacnoise wealthy.

Today, you can still arrive by boat. Several cruise operators offer trips from Athlone (20 kilometres north) that include a stop at Clonmacnoise. The approach from the water gives you the same view that medieval pilgrims saw: the round towers rising from the flat landscape, the cathedral dominating the skyline, the sense of a sacred city set apart from the ordinary world.

Even if you arrive by car, walk down to the riverbank. The Shannon here is wide and slow-moving, lined with reed beds and willow trees. In summer, swallows dart across the water. In winter, the floods transform the surrounding meadows into a shallow lake. The monks chose this site partly for its isolation — the river made it accessible, but the floodplain kept it separate.

The modern harbour is a floating pontoon just downstream from the ruins. It is used by the cruise boats and occasionally by private craft. There is no permanent mooring, but the site makes an excellent stop for anyone cruising the Shannon.

The Visitor Centre and Museum

The Office of Public Works manages Clonmacnoise through a visitor centre that opened in 1999. The building is modern but unobtrusive — a low structure that does not compete with the ruins. Inside, you will find exhibitions, a gift shop, toilets, and a small café.

The exhibition traces the history of Clonmacnoise from its founding to the present day. Highlights include: the original Cross of the Scriptures, displayed in a climate-controlled case; fragments of high crosses too damaged to display outdoors; a collection of grave slabs with their inscriptions deciphered; interactive displays explaining monastic daily life; and scale models showing the site at various periods.

The audio-visual show runs every half hour and provides essential context for understanding what you are about to see. Do not skip it — Clonmacnoise is confusing without background knowledge, and the twenty-minute film explains the layout and significance clearly.

The gift shop sells the usual souvenirs but also stocks serious books on Irish monasticism and early medieval art. Worth browsing if you want to go deeper.

Practical Information for Visiting Clonmacnoise

Getting There

Clonmacnoise is in County Offaly, about 20 kilometres south of Athlone and 25 kilometres north of Birr. By car, take the R357 from either direction — the site is well signposted. There is a large car park (€2 charge in summer).

Public transport is limited. The nearest bus stop is in Shannonbridge, about 3 kilometres away. From there, you can walk or arrange a taxi. Better options are to visit as part of a tour from Athlone or Galway, or to hire a car.

Opening Hours

Summer (May-September): 10:00 AM — 6:00 PM. Winter (October-April): 10:00 AM — 5:00 PM. Last admission 45 minutes before closing. The site is closed on Christmas Day and St. Stephen's Day.

Admission Prices (2026)

Adults: €8, Seniors/Students: €6, Children under 12: Free, Families: €20.

What to Wear and Facilities

The site is entirely outdoors with no shelter. The floodplain means it can be windy and exposed. Sturdy shoes are essential — the ground is uneven and can be muddy after rain. Bring waterproofs even if the forecast looks good.

Facilities include toilets in the visitor centre, a small café serving coffee and light snacks, and picnic tables near the car park. There is no accommodation on site — nearest options are in Athlone or Ballinasloe.

Best time to visit: Early morning offers the best light for photography and the fewest crowds. The site rarely gets uncomfortably busy, but summer afternoons can see several coach tours arriving simultaneously. Winter visits have a particular atmosphere — the mist rising from the Shannon, the crows wheeling around the towers, the sense of ancient solitude.

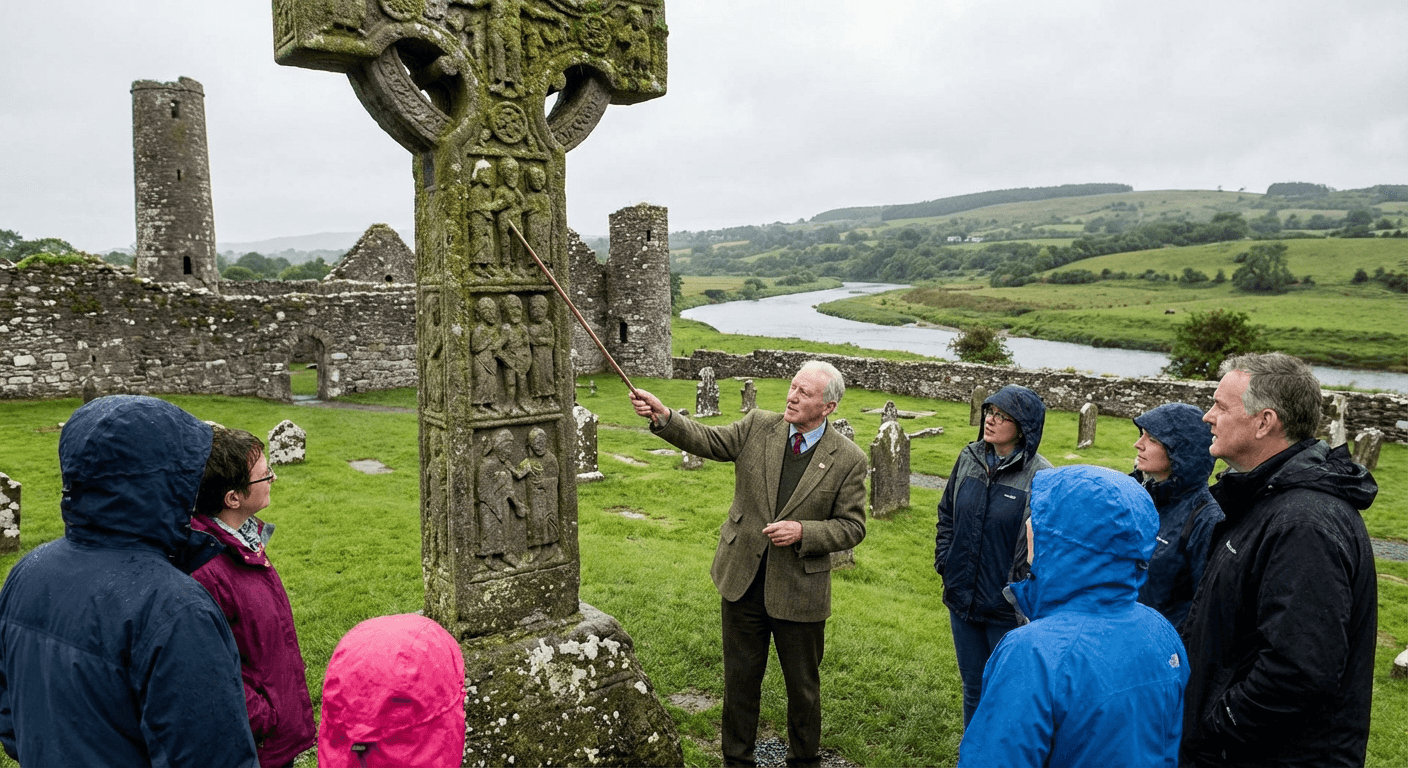

Why You Need a Historical Expert at Clonmacnoise

Here is the truth about Clonmacnoise: without context, it is a collection of old stones in a field. The ruins are impressive, but they do not speak for themselves. You need someone who can read the grave slabs, decode the crosses, and explain why this place mattered enough for kings to fight over it for six centuries.

A Historical Expert who specialises in early medieval Ireland will transform your visit. They will show you the Viking influence in the cross carvings. They will read the Latin inscriptions on the grave slabs and tell you about the people buried beneath — abbots, scholars, pilgrims who travelled from Germany and France. They will explain the difference between a "scriptorium" and a "refectory," and why the round towers mattered for more than just defence.

More importantly, they will connect Clonmacnoise to the broader story of Sacred Ireland. This site does not exist in isolation. It was part of a network that included Glendalough, Skellig Michael, and the Rock of Cashel — a network that preserved learning through the Dark Ages and created the artistic traditions that define Irish culture. Your guide can show you how the monks of Clonmacnoise influenced the Book of Kells, how their annals recorded Viking raids and Norman invasions, how their high crosses set the standard for Irish stone carving.

The practical advantages matter too. Your guide handles tickets, knows the best times to avoid crowds, and can arrange special access (the round tower climb, for example, requires coordination with site staff). They know where to park, where to eat, and how to combine Clonmacnoise with other sites into a meaningful day trip.

Browse Historical Experts in County Offaly on Irish Getaways and book someone who can bring the Crossroads of Ireland to life.

Conclusion

Clonmacnoise is not a place for rushing. The site covers several acres, the history spans a millennium, and the atmosphere demands slow contemplation. Come prepared to walk, to imagine, and to learn.

Stand in the cathedral and picture the monastic community at prayer. Walk around the high crosses and read the biblical stories carved in stone. Climb the round tower if you can, and look out across the Shannon at the landscape that made this place possible. Visit Temple Ciarán and remember the young saint who founded an empire of learning on a riverbank in the Irish midlands.

This is Sacred Ireland at its most profound — not the dramatic peaks of Croagh Patrick or the remote isolation of Skellig Michael, but the quiet endurance of a community that chose to build something eternal at the crossroads of a nation. For more on Ireland's monastic heritage, see our complete guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

For a complete overview of Ireland’s most important ancient and spiritual locations, see our master guide to Sacred Ireland.

Related Sacred Sites

Its collection of high crosses is among the finest in Ireland, rivalled only by sites like Glendalough.

While Clonmacnoise was a centre of learning, the Rock of Cashel was a centre of power.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.