Holy Wells of Ireland: How to Find and Respect These Ancient Healing Sites

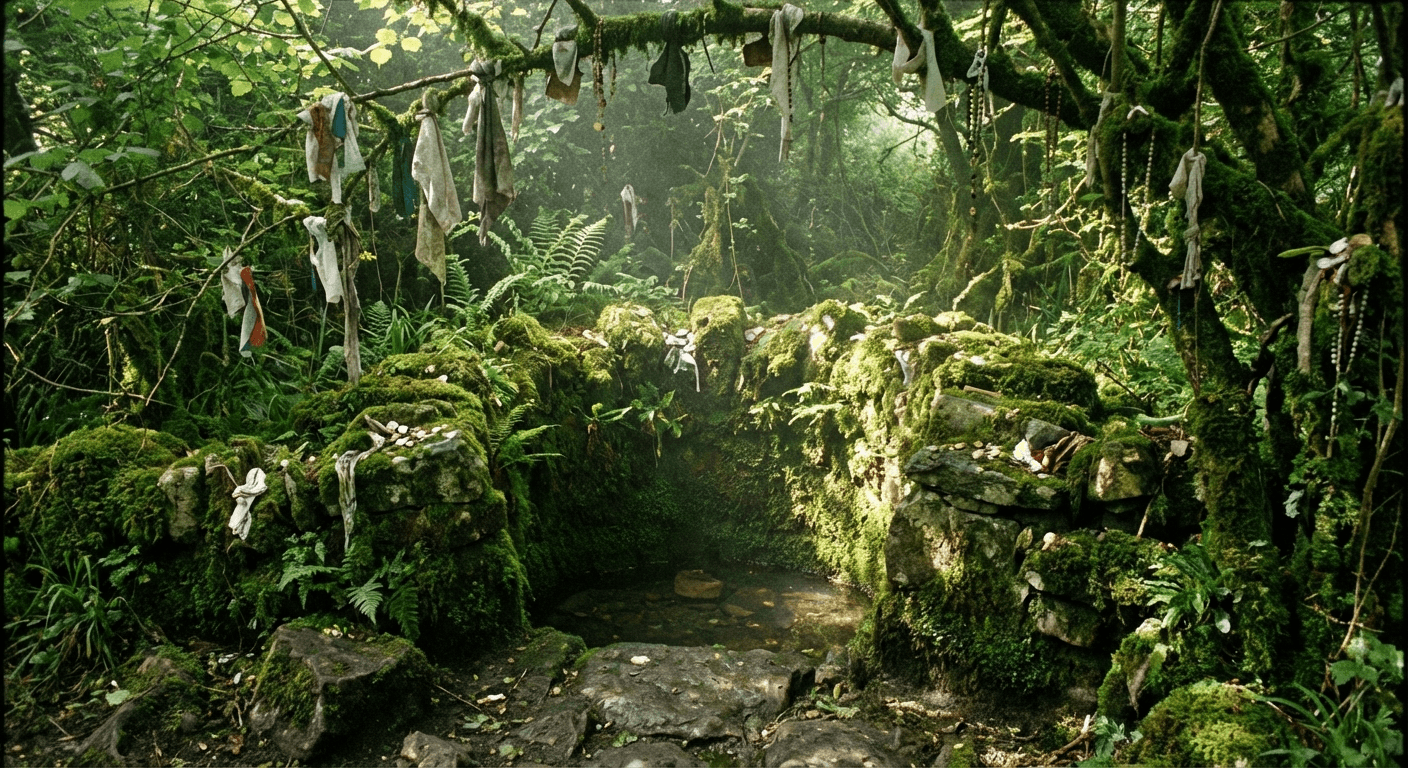

There are thousands of them scattered across Ireland — hidden in hedgerows, tucked behind modern housing estates, marked only by a rusted iron gate or a stone cross worn smooth by centuries of pilgrims' hands. Holy wells. Tobar in Irish. Places where the veil between worlds is said to grow thin, where water bubbles up from the earth with properties that defy scientific explanation, where patterns and rituals have remained unchanged since before Saint Patrick arrived.

The holy wells of Ireland represent one of the most enduring and least understood aspects of Irish spirituality. These are not tourist attractions in the conventional sense. Many have no car parks, no visitor centres, no signage. Some are on private farmland, accessible only by asking permission. Others sit in plain sight, passed daily by commuters who have no idea that the nondescript pool beside the road was once the destination for thousands of annual pilgrims seeking cures for everything from sore eyes to infertility.

This guide explains what holy wells are, why they matter, how to find them, and — crucially — how to visit them respectfully. This is not just about ticking off another "attraction" on your Irish itinerary. The holy wells are living traditions, still visited by local people who maintain the old ways. As visitors, we have a responsibility to understand the customs, respect the privacy of those who come to pray, and leave these fragile sites exactly as we found them. This is part of our comprehensive guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

What Is a Holy Well? Pagan Springs and Christian Sanctity

At its simplest, a holy well is a natural spring or well that has acquired religious significance. The water might emerge from limestone bedrock, bubble up through peat, or flow from some underground source that never freezes in winter and never runs dry in summer. In a country where clean water was historically precious, any reliable spring was valuable. When that spring produced "miraculous" cures or was associated with a saint, it became holy.

The origins of Ireland's holy wells stretch back to pre-Christian times. The Celtic peoples revered water sources as portals to the Otherworld — places where the gods might be contacted, where divination was possible, where healing could be sought. The early Christian missionaries did not try to suppress these beliefs. Instead, they baptised them, literally and figuratively. The pagan spring became Saint Brigid's Well, Saint Patrick's Well, Saint Ciarán's Well. The old rituals were adapted — the sunwise circumambulation became a Christian pattern, the offerings to pagan deities became prayers to the Virgin Mary.

This fusion created something uniquely Irish. The holy wells are neither purely pagan nor purely Christian. They are both simultaneously, layered together over centuries until the distinction becomes meaningless. A modern visitor might encounter a well where people still leave cloth "clooties" tied to nearby trees — an ancient Celtic practice — while reciting the Rosary — a Catholic devotion. The combination would shock a theologian. To the local people, it is simply the way things have always been done.

Key Characteristics of Holy Wells

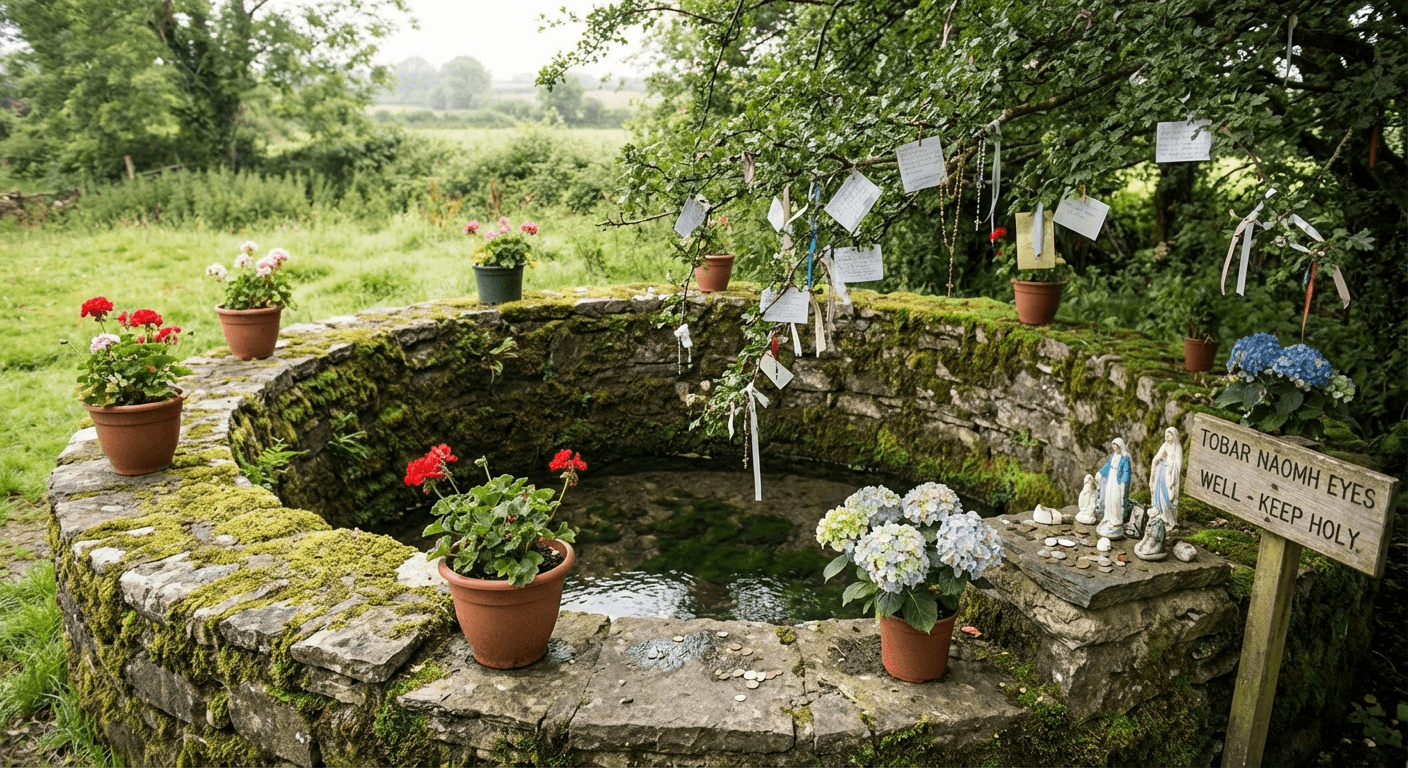

Patron saints: Most wells are associated with a specific saint, often the founder of a local monastery or a healer-saint like Brigid or Patrick. Cures: Each well traditionally specialises in curing specific ailments — eye problems, skin conditions, infertility, mental illness. Patterns: The ritual of visiting a well, known as "paying rounds" or "making a station," involves specific prayers, circumambulations, and offerings. Pattern days: Most wells have a specific day (usually the saint's feast day) when pilgrims gather for communal celebration. Offerings: Pins, coins, cloth strips, rosaries, and other votive objects left as payment for cures received or prayers answered.

The Pattern: How to Pay Rounds at a Holy Well

If you visit a holy well without understanding the pattern, you are just looking at a hole in the ground. The pattern — the traditional sequence of prayers and movements — transforms the visit into a spiritual practice that has remained essentially unchanged for a thousand years.

The basic structure of a pattern varies by location, but most include these elements:

The Approach: Pilgrims traditionally approach the well in silence, or at least with reverence. At some sites, you remove your shoes. At others, you approach on your knees for the final few metres. Observe what local people are doing and follow their lead.

The Rounds: The core of the pattern involves walking around the well a specific number of times — usually three, seven, or nine, always sunwise (clockwise). Each round is accompanied by specific prayers, usually the Our Father, Hail Mary, and Glory Be, repeated a set number of times. At some wells, you walk barefoot. At others, you walk on your knees.

The Water: After completing the rounds, you collect water from the well. This might involve drinking it, bathing affected body parts in it, or bringing it home in a bottle. Some wells require you to drink directly from the spring using a specific cup kept at the site. Never use your hands — always use the provided cup or a clean vessel.

The Offerings: You leave something at the well. Traditionally, this was a coin, a pin, or a strip of cloth torn from your clothing. Modern pilgrims might leave rosaries, holy cards, or written prayers. The cloth strips (called "clooties") are tied to nearby trees or bushes. The coin is dropped into the well or placed on a ledge.

The Departure: You leave quietly, without looking back. Some traditions say you must not speak until you are a certain distance from the well. Others require you to complete the pattern on three consecutive days, or three consecutive Fridays, or nine consecutive days.

Important: If you are not a believer, you can still observe these customs out of respect. The local people do not expect visitors to share their faith, but they do expect respect for the tradition. Watch, learn, and follow the lead of those who know the proper form.

Finding Holy Wells: Maps, Word of Mouth, and Getting Lost

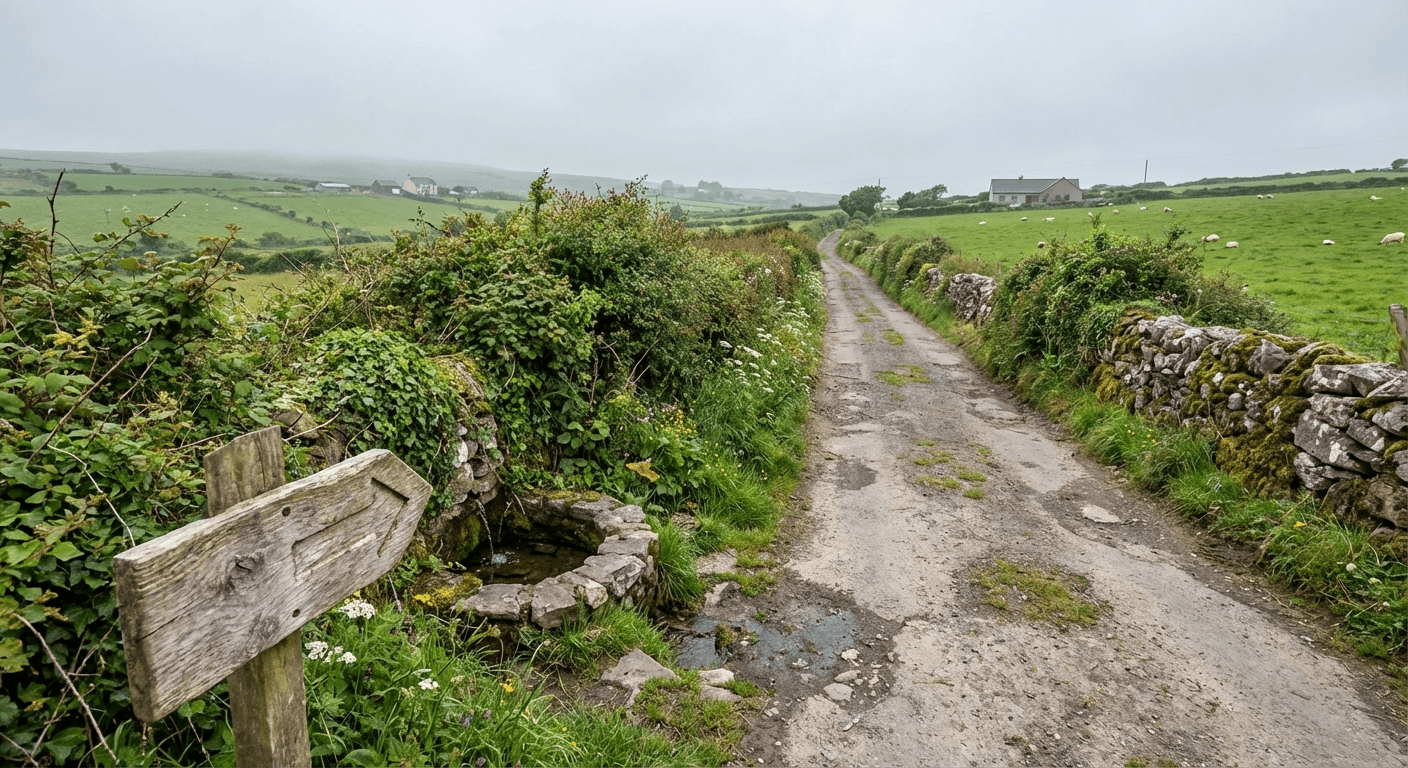

Unlike Glendalough or the Rock of Cashel, holy wells are rarely signposted for tourists. Finding them requires effort, local knowledge, and a willingness to explore. Here are the best approaches:

Ordnance Survey Maps: The most reliable method. Irish OS maps mark holy wells with a specific symbol — a small blue dot with a cross. The maps also show the townland names, which often contain clues (Tobar = well, Kill = church, Cill = church). A well in the townland of Toberpatrick is almost certainly Saint Patrick's Well.

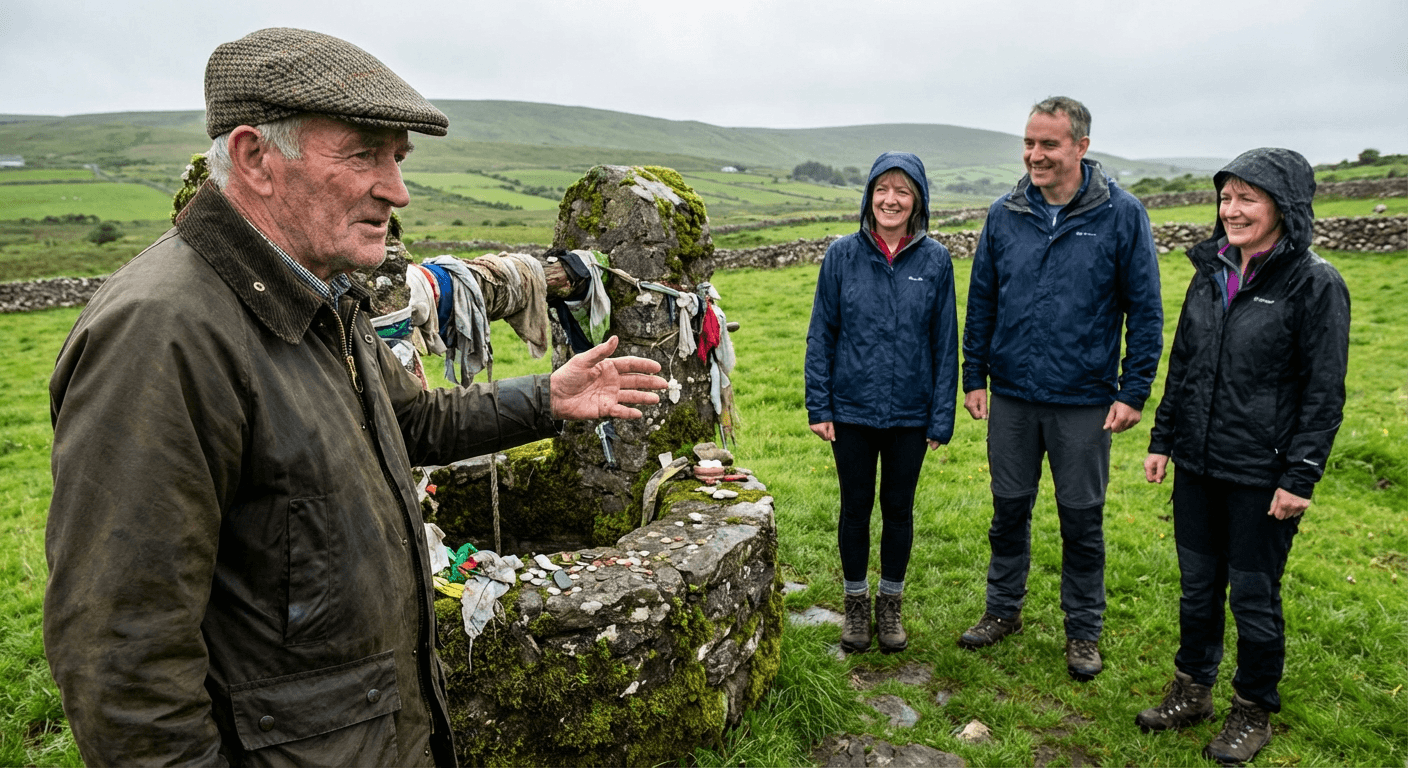

Local Knowledge: The best source. Ask in pubs, post offices, and shops. Not everyone will know — holy wells are often secrets kept by the older generation — but someone always knows. Be respectful. Explain that you are interested in the tradition, not just ticking off a sight. Offer to buy a pint or a cup of tea for the information.

Online Databases: Several websites catalog Ireland's holy wells, though accuracy varies. The National Folklore Collection at University College Dublin has extensive records. Local history societies often publish pamphlets or maintain websites for their areas.

Once You Know the General Location: Getting there is the next challenge. Many holy wells are on private farmland. Always ask permission from the landowner. Most will grant it gladly — they are proud of their well — but some may refuse, or ask you to visit at specific times. Respect their wishes absolutely.

What to Bring

Sturdy waterproof boots (fields are often muddy). A map and compass or GPS (mobile signals are unreliable in rural areas). Water and snacks. A camera (ask permission before photographing people at prayer). An offering (a coin, a strip of cloth, or a small religious object). Patience and flexibility.

Notable Holy Wells Worth Seeking Out

There are over 3,000 recorded holy wells in Ireland. Most are simple, unmarked springs. A few have developed into elaborate sites with shrines, statues, and annual festivals. Here are some of the most significant:

Saint Patrick's Well, Liscannor (County Clare): One of the most visited holy wells in Ireland, located near the Cliffs of Moher. The well is housed in a small stone building beside the ruins of a medieval church. Pattern day is March 17th (Saint Patrick's Day), when thousands of pilgrims visit.

Saint Brigid's Well, Kildare (County Kildare): Associated with Ireland's most beloved female saint. The well is in the grounds of a convent, accessible through a formal garden. The site includes a medieval church, a round tower, and the famous perpetual flame tended by the Brigidine sisters.

Tobernalt Holy Well (County Sligo): A beautifully preserved well in a natural woodland setting. The site includes a Mass rock from the Penal Times, when Catholic worship was illegal and Mass had to be celebrated in secret outdoor locations. Pattern day is July 15th.

Saint Declan's Well, Ardmore (County Waterford): Associated with one of Ireland's pre-Patrician saints, who supposedly brought Christianity to the Déise region before Patrick arrived. The well is part of a larger ecclesiastical site that includes a cathedral, round tower, and oratory.

Saint Ciarán's Well, Clonmacnoise (County Offaly): Located near the famous monastic site Clonmacnoise, this well is associated with the founder of Clonmacnoise. It is still visited by pilgrims completing the pattern at the monastery.

Gougane Barra (County Cork): A stunning location where Saint Finbarr founded his first monastery on a lake island. The holy well is on the mainland, but the entire valley has sacred associations. One of the most beautiful sites in Ireland.

Respect and Etiquette: Being a Responsible Visitor

Holy wells are not museums. They are active religious sites, used by local people for prayer, healing, and spiritual sustenance. As visitors, we have a responsibility to ensure our presence does not disrupt these practices or damage these fragile sites.

Do

Ask permission if the well is on private land. Observe local customs and follow the lead of regular visitors. Remove your hat when approaching the well. Keep voices low — many people come to pray in silence. Take photographs only with permission, and never of people at prayer without explicit consent. Leave an offering, even if you are not religious — a coin, a pebble, a strip of cloth. Take all litter with you. Close gates behind you when crossing farmland.

Do Not

Remove offerings left by others — those clooties and coins belong to the well. Drink the water unless you are certain it is safe (some wells are contaminated). Bathe in the well itself — use the water you collect away from the source. Build cairns or stone piles — this is a modern tourist practice that damages sites. Leave modern trash as offerings — plastic ribbons, aluminum foil, and synthetic materials are pollutants. Visit on pattern days unless you are prepared for crowds and willing to participate respectfully. Treat the site as a backdrop for Instagram photos without understanding its significance.

The Golden Rule: Holy wells belong to the local community, not to visitors. We are guests in these spaces. Act accordingly.

Why a Local Guide Makes All the Difference

You can find holy wells on your own. With good maps and determination, you will locate some of them. But here is what you will miss: the stories, the context, the living tradition that makes these places meaningful.

A Walking Guide or Local Cultural Guide who knows the area can transform your holy well experience. They know which wells are accessible and which are on private land where permission is tricky. They know the pattern for each well — the specific prayers, the correct number of rounds, the proper offerings. They can introduce you to the local people who maintain the wells, who might share stories you would never hear otherwise.

More importantly, they provide context. The holy wells do not exist in isolation. They are part of a landscape that includes ancient churches, monastic sites like Glendalough, sacred mountains like Croagh Patrick, and the countless other elements that make up Sacred Ireland. A knowledgeable guide can show you how the wells fit into this larger picture — how the water connects to the land, how the patterns connect to ancient pilgrimage routes, how the traditions have survived centuries of social change.

The practical benefits matter too. Your guide handles permissions, knows the best times to visit (avoiding pattern days if you want solitude, or timing your visit to experience the communal celebration), and can combine holy wells with other sites into a meaningful itinerary. They know which wells are worth the effort and which are disappointing — not every marked well is maintained or accessible.

The Living Tradition: Holy Wells in Modern Ireland

In an increasingly secular Ireland, you might expect holy wells to be fading traditions, maintained only by the elderly and ignored by the young. The reality is more complex. While attendance at pattern days has declined in some areas, other wells are seeing renewed interest. The COVID-19 pandemic actually increased visits to outdoor holy sites, as people sought spiritual connection outside locked churches.

Local communities remain fiercely protective of their wells. In many areas, the well is still cleaned and decorated before pattern day by volunteers who have inherited the responsibility from their parents and grandparents. The offerings continue — not just coins and clooties, but modern additions like plastic rosaries, laminated prayer cards, and even photographs of loved ones seeking healing.

Archaeologists and historians are increasingly interested in holy wells as sources of information about Irish spirituality, landscape use, and social history. Some wells are being formally surveyed and documented for the first time. Others are under threat from development, pollution, or simple neglect — prompting conservation efforts by heritage organisations.

For visitors, the holy wells offer something rare: authentic connection to ancient traditions that have not been sanitised for tourism. When you visit a holy well, you are participating in a practice that your ancestors — and countless generations of Irish people — have performed for thousands of years. That continuity matters. It is a form of time travel, a way of touching the deep past.

Conclusion

The holy wells of Ireland are not for everyone. They require effort to find, knowledge to appreciate, and sensitivity to visit respectfully. There are no cafés, no gift shops, no convenient car parks. You will get muddy, you will get lost, and you might encounter locals who view your presence with suspicion.

But for those willing to make the effort, the holy wells offer rewards that no conventional tourist attraction can match. These are places where the ancient and the modern, the pagan and the Christian, the local and the universal, meet and merge. They are living connections to the spiritual landscape of Ireland — a landscape that shaped the culture, art, and identity of a nation.

Visit with respect. Learn the patterns. Listen to the stories. And remember that you are a guest in spaces that have been sacred since long before your arrival.

For more on Ireland's sacred sites, from Skellig Michael to Clonmacnoise, from Croagh Patrick to the Rock of Cashel, see our complete guide to Sacred Ireland: Monastic Sites, Holy Wells & Ancient Pilgrimages — the master hub.

For a complete overview of Ireland’s most important ancient and spiritual locations, see our master guide to Sacred Ireland.

Related Sacred Sites

Many wells are associated with early Christian saints and are often found near monastic sites such as Glendalough.

The act of visiting a holy well is a small pilgrimage, much like the great annual climb up Croagh Patrick.

Table of Contents

Share this post

More from the Blog

Sea Kayaking in Donegal: Into the Coastline That Has No Equivalent

Donegal's northwest coastline is almost entirely inaccessible on foot. Sea kayaking opens the caves at Maghera, Slieve League's full cliff face, and shore no road reaches.

Kayaking the Cliffs of Moher: A View 700,000 Tourists Never Get

Over a million visitors walk the cliff path every year. Here's what the Cliffs of Moher look like from sea level — and why the difference is total.

Sea Kayaking Along the Dingle Peninsula: Paddling the End of the World

Paddle the sea caves, Blasket Sound, and wildlife-rich waters of Dingle — Ireland's most dramatic sea kayaking destination on the Wild Atlantic Way.